Cyborg Manifesto author and philosopher who explores the nature of reality discusses the science wars and climate activism

The history of philosophy is also a story about real estate.

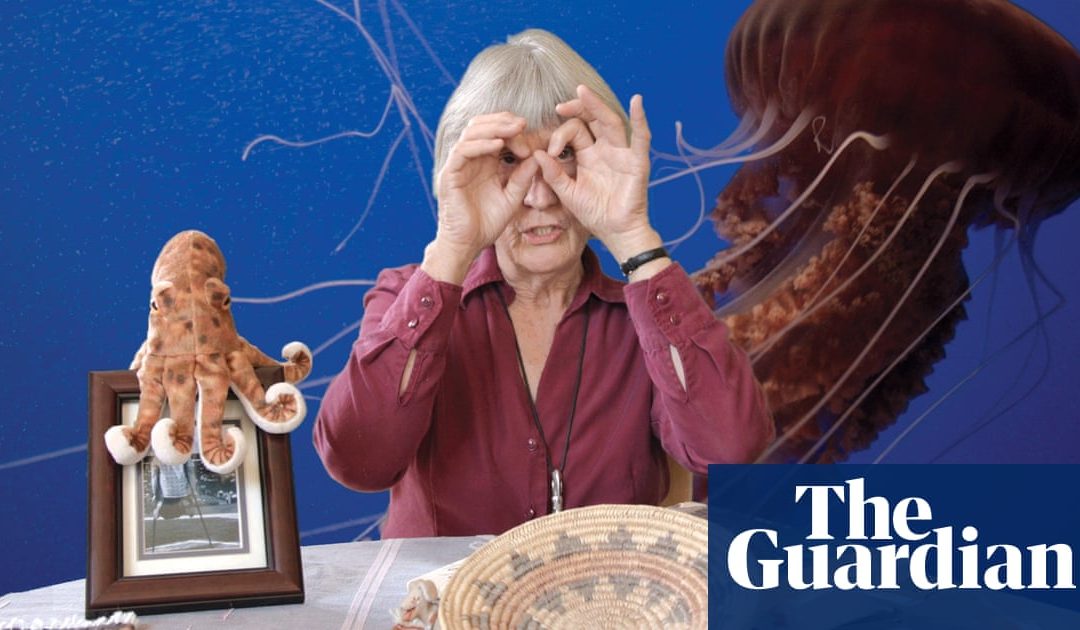

Driving into Santa Cruz to visit Donna Haraway, I cant help feeling that I was born too late. The metal sculpture of a donkey standing on Haraways front porch, the dogs that scramble to her front door barking when we ring the bell, and the big black rooster strutting in the coop out back the entire setting evokes an era of freedom and creativity that postwar wealth made possible in northern California.

Here was a counterculture whose language and sensibility the tech industry sometimes adopts, but whose practitioners it has mostly priced out. Haraway, who came to the University of Santa Cruz in 1980 to take up the first tenured professorship in feminist theory in the US, still conveys the sense of a wide-open world.

Haraway was part of an influential cohort of feminist scholars who trained as scientists before turning to the philosophy of science in order to investigate how beliefs about gender shaped the production of knowledge about nature. Her most famous text remains The Cyborg Manifesto, published in 1985. It began with an assignment on feminist strategy for the Socialist Review after the election of Ronald Reagan and grew into an oracular meditation on how cybernetics and digitization had changed what it meant to be male or female or, really, any kind of person. It gained such a cult following that Hari Kunzru, profiling her for Wired magazine years later, wrote: To boho twentysomethings, her name has the kind of cachet usually reserved for techno acts or new phenethylamines.

The cyborg vision of gender as changing and changeable was radically new. Her map of how information technology linked people around the world into new chains of affiliation, exploitation and solidarity feels prescient at a time when an Instagram influencer in Berlin can line the pockets of Silicon Valley executives by using a phone assembled in China that contains cobalt mined in Congo to access a platform moderated by Filipinas.

Haraways other most influential text may be an essay that appeared a few years later, on what she called situated knowledges. The idea, developed in conversation with feminist philosophers and activists such as Nancy Hartsock, concerns how truth is made. Concrete practices of particular people make truth, Haraway argued. The scientists in a laboratory dont simply observe or conduct experiments on a cell, for instance, but co-create what a cell is by seeing, measuring, naming and manipulating it. Ideas like these have a long history in American pragmatism. But they became politically explosive during the so-called science wars of the 1990s a series of public debates among scientific realists and postmodernists with echoes in controversies about bias and objectivity in academia today.

Haraways more recent work has turned to human-animal relations and the climate crisis. She is a capacious yes, and thinker, the kind of leftist feminist who believes that the best thinking is done collectively. She is constantly citing other people, including graduate students, and giving credit to them. A recent documentary about her life and work by the Italian film-maker Fabrizio Terranova, Storytelling for Earthly Survival, captures this sense of commitment, as well as her extraordinary intellectual agility and inventiveness.

At her home in Santa Cruz, we talked about her memories of the science wars and how they speak to our current post-truth moment, her views on contemporary climate activism and the Green New Deal, and why play is essential for politics.

We are often told we are living in a time of post-truth. Some critics have blamed philosophers like yourself for creating the environment of relativism in which post-truth flourishes. How do you respond to that?

Our view was never that truth is just a question of which perspective you see it from.

[The philosopher] Bruno [Latour] and I were at a conference together in Brazil once. (Which reminds me: if people want to criticize us, it ought to be for the amount of jet fuel involved in making and spreading these ideas! Not for leading the way to post-truth.)

Anyhow. We were at this conference. It was a bunch of primate field biologists, plus me and Bruno. And Stephen Glickman, a really cool biologist, took us apart privately. He said: Now, I dont want to embarrass you. But do you believe in reality?

We were both kind of shocked by the question. First, we were shocked that it was a question of belief, which is a Protestant question. A confessional question. The idea that reality is a question of belief is a barely secularized legacy of the religious wars. In fact, reality is a matter of worlding and inhabiting. It is a matter of testing the holdingness of things. Do things hold or not?

Take evolution. The notion that you would or would not believe in evolution already gives away the game. If you say, Of course I believe in evolution, you have lost, because you have entered the semiotics of representationalism and post-truth, frankly. You have entered an arena where these are all just matters of internal conviction and have nothing to do with the world. You have left the domain of worlding.

The science warriors who attacked us during the science wars were determined to paint us as social constructionists that all truth is purely socially constructed. And I think we walked into that. We invited those misreadings in a range of ways. We could have been more careful about listening and engaging more slowly. It was all too easy to read us in the way the science warriors did. Then the rightwing took the science wars and ran with it, which eventually helped nourish the whole fake-news discourse.

Your PhD is in biology. How do your scientist colleagues feel about your approach to science?

To this day I know only one or two scientists who like talking this way. And there are good reasons why scientists remain very wary of this kind of language. I belong to the Defend Science movement and in most public circumstances I will speak softly about my own ontological and epistemological commitments. I will use representational language. I will defend less-than-strong objectivity because I think we have to, situationally.

Is that bad faith? Not exactly. Its related to [what the postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has called] strategic essentialism. There is a strategic use to speaking the same idiom as the people that you are sharing the room with. You craft a good-enough idiom so you can work on something together. I go with what we can make happen in the room together. And then we go further tomorrow.

In the struggles around climate change, for example, you have to join with your allies to block the cynical, well-funded, exterminationist machine that is rampant on the Earth. I think my colleagues and I are doing that. We have not shut up, or given up on the apparatus that we developed. But one can foreground and background what is most salient depending on the historical conjuncture.

What do you find most salient at the moment?

What is at the center of my attention are land and water sovereignty struggles, such as those over the Dakota Access pipeline, over coal mining on the Black Mesa plateau, over extractionism everywhere. My attention is centered on the extermination and extinction crises happening at a worldwide level, on human and non-human displacement and homelessness. Thats where my energies are. My feminism is in these other places and corridors.

What kind of political tactics do you see as being most important for young climate activists, the Green New Deal, etc?

The degree to which people in these occupations play is a crucial part of how they generate a new political imagination, which in turn points to the kind of work that needs to be done. They open up the imagination of something that is not what [the ethnographer] Deborah Bird Rose calls double death extermination, extraction, genocide.

Now, we are facing a world with all three of those things. We are facing the production of systemic homelessness. The way that flowers arent blooming at the right time, and so insects cant feed their babies and cant travel because the timing is all screwed up, is a kind of forced homelessness. Its a kind of forced migration, in time and space.

This is also happening in the human world in spades. In regions like the Middle East and Central America, we are seeing forced displacement, some of which is climate migration. The drought in the Northern Triangle countries of Central America [Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador] is driving people off their land.

So its not a humanist question. Its a multi-kind and multi-species question.

Whats so important about play?

Play captures a lot of what goes on in the world. There is a kind of raw opportunism in biology and chemistry, where things work stochastically to form emergent systematicities. Its not a matter of direct functionality. We need to develop practices for thinking about those forms of activity that are not caught by functionality, those which propose the possible-but-not-yet, or that which is not-yet but still open.

It seems to me that our politics these days require us to give each other the heart to do just that. To figure out how, with each other, we can open up possibilities for what can still be. And we cant do that in a negative mood. We cant do that if we do nothing but critique. We need critique; we absolutely need it. But its not going to open up the sense of what might yet be. Its not going to open up the sense of that which is not yet possible but profoundly needed.

The established disorder of our present era is not necessary. It exists. But its not necessary.

A longer version of this conversation will appear in a forthcoming issue of Logic, a magazine about technology. To learn more, or subscribe, visit logicmag.io.

-

The documentary Donna Haraway: Story Telling For Earthly Survival is now available to stream on Amazon, iTunes, and Vimeo, as well as on DVD via Icarus Films.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/20/donna-haraway-interview-cyborg-manifesto-post-truth

Recent Comments