Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Over the years, one financial crisis after another has ruined – or profited – those caught in the middle of it. The pay and benefits of UK residents is still being affected by the latest crisis of a decade ago.

So when has financial advice eased, exacerbated, or even created these downturns?

Researchers at the universities of Southampton, Edinburgh, Lancaster and Manchester – funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council – have explored the history of financial advice, and how it is represented in culture. The findings are part of a free, online course.

Professor Nicky March, principal investigator on the project, has picked out some examples from art and literature and explains what they tell us.

The South Sea Bubble

The failure of the South Sea Company was the crisis that shaped our understanding of the dangers of speculative bubbles.

Yet many of its satirical representations focus on the deceptions of those involved and speak of a deep mistrust toward the emerging financial profession.

Image copyright Lewis Walpole Library, Yale

Image copyright Lewis Walpole Library, Yale The cartoon The Bubblers bubbl’d or the Devil Take the Hindmost, for example, depicts stockjobbers passing stock certificates that flutter down from above in a crazed dance from which they cannot free themselves, and in which the only option is to try to pass the worthless paper to the greater fool beside them.

Investors in the 1720s relied on stockjobbers, rumours and friends and relatives for their financial advice.

Fraud and imperial fantasies

Even when the genre of financial advice had appeared, in newspaper columns and guidebooks, it was not always trustworthy.

The financial boom of the 1820s provided investors with a dizzying range of new investments, especially those with an appetite for imperial adventures. The financial advice manuals that now did exist conservatively warned against these investments so new writers filled the gap.

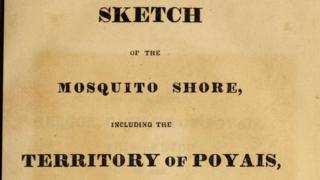

A speculative genre of financial advice emerged, one that talked up the untold wealth to be made from new discoveries, innovations, and technologies. One of the most notorious examples was Thomas Strangeways’ 1822 Sketch of the Mosquito Shore.

Image copyright Archive.org

Image copyright Archive.org The book was authored by the soldier and adventurer Gregor MacGregor but its glowing account of the resources and climate of the new nation of Poyais was entirely fraudulent.

It was targeted chiefly at the settlers he hoped to lure to his utopia, but the book underpinned MacGregor’s efforts to float a Poyais loan on the London market and he raised over £50,000 before the scam was exposed.

The Brontes and railway mania

Britain went mad for railway shares in the 1840s. In their Haworth parsonage, the Bronte sisters – Charlotte, Emily, and Anne – inherited shares in the York and North Midland Railway.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Charlotte’s letters reveal how the sisters navigated the market. Emily took charge of their investments, “carefully reading every paragraph and every advertisement in the newspapers that related to rail-roads”. But the press, full of hype for the railways, did not give the best advice.

Charlotte wanted to sell out before it was too late, but could not persuade “headstrong” Emily, and eventually gave way. Her concerns were vindicated when the market collapsed. Charlotte learnt from the mistake. She took the advice of her publisher in 1849 and invested the royalties from her novel Shirley in Consols (perpetual government bonds).

A self-fulfilling prophecy

Thomas Lawson (1857-1925) was at one point the sixth richest man in America. He made his fortune as a stock promoter, organising large corporate mergers. However, he was soon sick of what he saw as the corrupt stranglehold that a clique of big businessmen had on the American economy.

Image copyright History of Financial Advice

Image copyright History of Financial Advice Instead he turned to muckraking journalism, and in 1906 published Frenzied Finance. It was a searing exposé of the scandal surrounding the Amalgamated Copper deal.

He soon realised that journalism does not pay as well as finance, so he returned to stock promotion. This time he tried to move the market not by insider dealing or an advice manual, but by writing a sensationalist novel, Friday the Thirteenth (1907).

It predicted an apocalyptic crash of the stock market. His avid readers took his warnings at face value, and ended up creating the real world the financial panic that the fiction had imagined – and Lawson pocketed the profit.

The Wall Street Crash

At the opening of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), the narrator, Nicky Carraway, recalls buying “a dozen volumes on banking and credit and investment securities”.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images In the 1920s, many Americans likewise devoured guides to Wall Street speculation in the hope of following in the footsteps of the legendary financier J.P. Morgan, and came to regret it when prices on the New York Stock Exchange collapsed in the Great Crash of 1929 and they lost anything they had invested.

Fitzgerald would go on to write the definitive post-crash story, Babylon Revisited, in 1931. The “luck in the market” enjoyed by the protagonist in the 1920s boom allows him to live as “a sort of royalty, almost infallible, with a sort of magic around [him]”, until the market cleans him out.

Fitzgerald’s protagonist ultimately suffers a breakdown – a fate sadly shared by the author himself and his wife Zelda in the depression years that followed what the author called “the most expensive orgy in history”.

The apocalyptic 1970s

As inflation steadily rose throughout the 1970s, financial advice often took a decidedly apocalyptic turn. Howard Ruff’s How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years recommended buying gold, food and guns.

Image copyright History of Financial Advice

Image copyright History of Financial Advice The relationship between financial advice and disaster fiction also began to blur in this moment. Paul Erdman’s The Billion Dollar Sure Thing, which turned President Nixon’s recent closing of the gold window into a cold war thriller, was taken up by influential economists for offering the best explanation of how money worked in the new economy emerging from the 1970s.

Reading the charts

The stock price chart – with its upward and downward lines forming peaks and troughs that resemble the profile of a mountain range – is one of the most familiar ways of visualising the financial markets.

Many investment advice authors believe that the movements of prices reflect underlying natural laws and form recurring patterns that can be “charted” and exploited for profit.

Image copyright Matthew Cornford and David Cross

Image copyright Matthew Cornford and David Cross In their digital work Black Narcissus (2014), the British artists Matthew Cornford and David Cross track along a computer-generated mountain skyline mapped onto the historical undulations of the stock market in the period 2003-2013.

In this still from the work, the downward trend on the left, culminating in the vertiginous drop in the centre, corresponds to the global financial crisis of 2008. Here, the market quite literally falls off a cliff edge – one that very few people saw coming.

Read more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-47655991

Recent Comments