Silicon Valley is entering a new phase in its quest for diversity and inclusion in the technology industry. Some advocates call this part “the end of the beginning,” Code2040 CEO Karla Monterroso tells TechCrunch.

At first, advocates were focused on calling out the lack of diversity at tech conferences, pressuring companies to release diversity data and debunking the pipeline problem. Then the focus shifted to hiring heads of diversity and implementing unconscious bias training (more on this in our ‘Diversity and inclusion playbook‘, but it’s worth pointing out those things are on their own are not productive).

“We’re past the window dressing stage and now it’s time to talk about accountability, consequences, promotions and retention,” she says. “And what it means to prioritize things to make sure the industry is not inhospitable.”

While the diversity and inclusion movement has made some gains in the last few years, it has still suffered severe setbacks. On one hand, tech employees are recognizing their immense power when they speak up and organize. On the other hand, those accused of sexual harassment and misconduct are too often facing too few consequences. Meanwhile, people of color and women still receive too little venture funding, and tech companies are inching along at a glacial pace toward diverse representation and inclusion.

“I would characterize where we are now as a leap forward over the last 10 years and several steps sideways and a few steps backward,” Freada Kapor Klein, co-founder at Kapor Capital and the Kapor Center for Social Impact, tells TechCrunch. “[…] Any point you can make in a positive direction, there’s a countervailing negative. And similarly, any time you can raise a criticism, somebody can point to something hopeful.”

Plenty has been written about the problems regarding diversity and inclusion in the tech industry. Despite all sincere efforts to fix these D&I issues, it will never ultimately be fixed because the tech industry is a reflection of our society and all of its issues pertaining to race, gender and class.

That fact, however, does not mean there is no hope to be had. The future of the tech industry lies in the hands of everyday tech employees, new startup founders and investors with a fresh pair of eyes. And what’s become painfully clear is that commitment from the top is not optional.

But to get to the light at the end of the tunnel, the industry needs to come to terms with how it got to where it is today, the ineffectiveness of one-off initiatives like hiring a head of D&I and implementing a standalone unconscious bias training, and what it will take to get where it needs to go.

The old (white) boys club

Silicon Valley is a predominantly white, male industry that is notoriously bad at welcoming and celebrating people from diverse backgrounds. This old boys club has put people of color and women at a disadvantage since the earliest days of the industry, and it continues to do so.

The current movement for diversity and inclusion started more than 10 years ago. At the time, there was talk about the lack of gender representation at tech conferences and the old boys club.

In his 2007 essay, “The Old Boys Club is for Losers,” Anil Dash, current Glitch CEO and then-co-founder of ThinkUp, the first analytics tool for social media, describes how those who defend the status quo of the white male in tech are defending a culture of failure. He argues: “Those who are reaching out to include all members of their community, who are seeking out new ideas and voices, are not only winning, they’re the only ones who will continue to win. You may succeed in defending the boys-only nature of your treehouse. But you’ll be dooming yourselves to irrelevance.”

In 2019, many people would welcome Dash’s take. But 2007 mainstream techies had a different understanding of diversity — so different that Dash was convinced hitting publish meant the end of his time in the tech industry, he tells TechCrunch.

“I was lucky enough to have a platform and then a profile to be able to say something,” Dash says. “I was also convinced that was the end of my career. I was like, ‘well, the hell with this, I’m done. I’m leaving San Francisco so I might as well burn some bridges.’ It’s funny now, because I think a lot of people would say there’s an old boys club in Silicon Valley. And it’s very exclusionary, and these are things we’ve got to tackle.”

Dash says he remembers exactly where he was sitting when he hit publish on the post. That’s because he thought no one would let him back into the industry.

“Fortunately, that has turned out to not be the case,” Dash says. “The Overton window has shifted a little bit in a way that is interesting and meaningful. At the same time, the problem hasn’t shifted. The difference is that we can talk about the problem, but that doesn’t mean we’re fixing the problem.”

Ellen Pao, co-founder at Project Include who was thrust into the spotlight during her lawsuit against Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byer, agrees. In 2012, Pao filed a lawsuit against her then-employer alleging gender discrimination and workplace retaliation. In 2015, a jury denied Pao’s claims of discrimination.

“When I sued, people called me outright crazy and treated me like a liar,” Pao tells TechCrunch. “Apparently that was the first time people were really hearing about it in a public light and they couldn’t process it. Today, so many people have told their stories and so many people have called attention to the problem that people are admitting it’s a problem.”

What’s different today is that the attitudes have changed from “let’s ignore it to let’s do something about it,” she says.

BOSTON, MA – DECEMBER 10: Entrepreneur, investor, writer Ellen Pao speaks on stage during Massachusetts Conference For Women at Boston Convention & Exhibition Center on December 10, 2015 in Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo by Marla Aufmuth/Getty Images for Massachusetts Conference for Women)

“The problem is not that much has really been done about it,” Pao says. “Companies are treating it as a PR crisis and strategy. It’s not an operational imperative to them so you don’t see much change. You see the constant problems coming up again and again.”

Pao points to Uber, which eventually ousted its co-founder Travis Kalanick as CEO following damning allegations from engineer Susan Fowler regarding sexual harassment at the company. Pao thinks the company really hasn’t changed that much despite having a new CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, in place.

“It’s not the same horrible problems, but you still don’t see a lot of diversity,” she says.

And then there’s Tesla, which Pao calls a “trash fire.”

Last year, black Tesla factory workers described a culture of racism and discrimination at the electric car maker’s factory in Fremont, Calif.

“I think there’s still a ton of work to do,” Pao says. “The change in attitude and the fact that people are actually responding to people sharing their experiences is a huge change, but it’s far from sufficient.”

Lip service

When Google released the industry’s first diversity report in 2014, it kickstarted a diversity and inclusion strategy rooted very little in action. Today, many people refer to that phenomena as lip service, which is when people talk the talk but don’t walk the walk.

In 2014, Google reported it was 61.3 percent white and 69.4 percent male. Fast forward to today, and Google is 54.4 percent white and 68.4 percent male. The numbers have barely moved over the years. Looking at both FAANG (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) and A-PLUS (Airbnb, Pinterest, Lyft, Uber and Slack) companies today, tech employees are still predominantly white and Asian.

At Facebook, there has been little change to its employee demographics in terms of the proportion that underrepresented minorities make up of the entire employee population. But Facebook Chief Diversity Officer Maxine Williams points out that there has been quite a lot of change within individual groups. For example, Williams tells TechCrunch that Facebook has increased the number of black women by 25x and black men by 10x over the last five years.

“There has been a lot of change,” Williams says. “Has there been as much as we want? No. And I certainly think we have the issue of when we started focusing on D&I in a very deliberate way. The company was already nine years old with thousands of people working here. The biggest takeaway is that the later you start, the harder it is.”

That’s the general state of the tech industry as a whole. While there has been some improvement in representation at these tech companies, there has not been nearly enough.

“I do think diversity reports hold them a little bit accountable,” Pao says. “It looks bad if they go backward. I do think it’s important because they should be looking at all of these numbers internally. But it’s unfortunate that they really look to the press to guide their strategy and attention.”

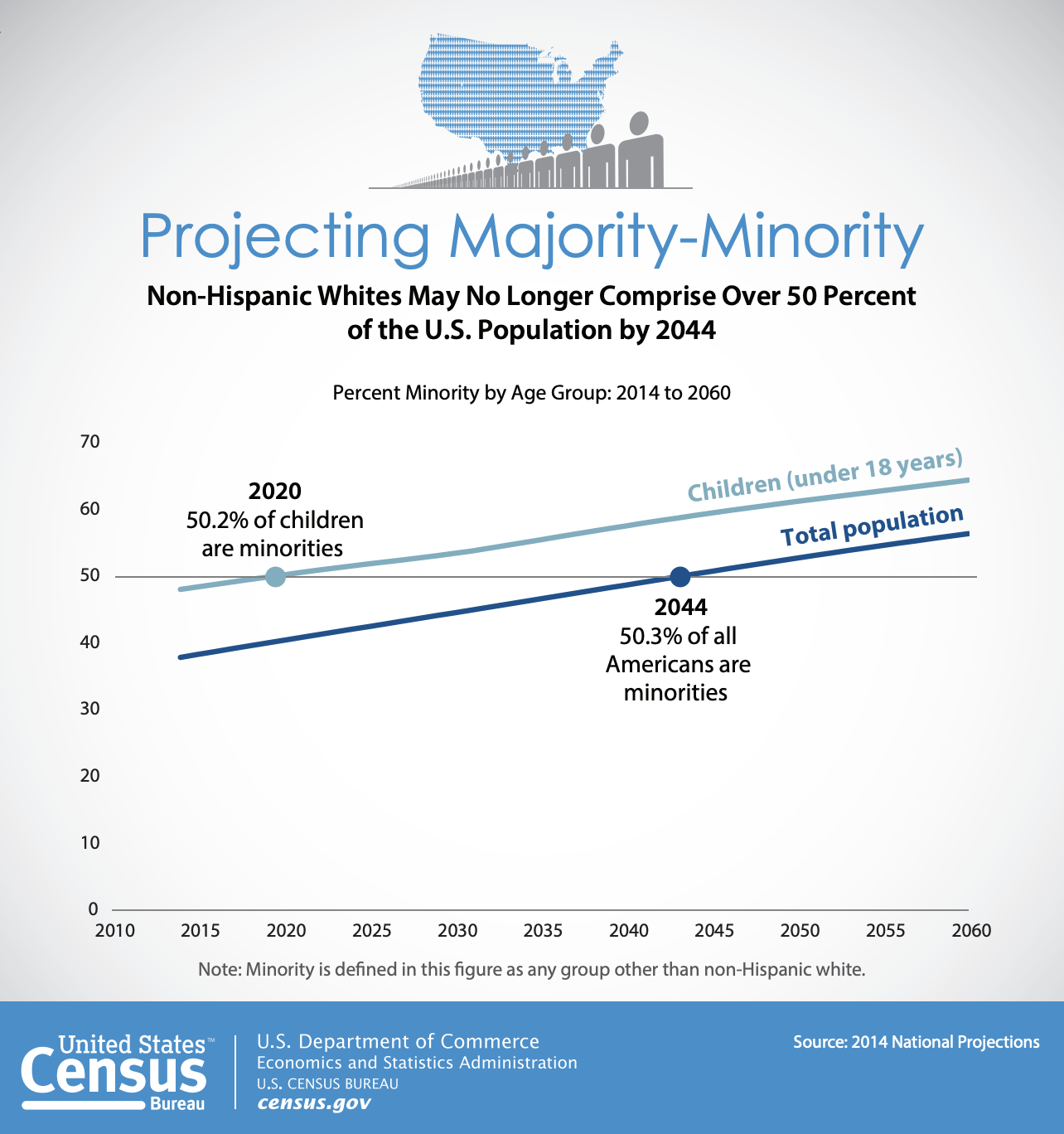

Where these numbers need to be, according to Pao, is at 13 percent for black employee representation and 17 percent for Latinx representation in order to reflect the demographics of the U.S. population.

In her work with startups via Project Include, Pao advises them to set 10-10-5-45 targets. The first two are to aim for 10 percent black and 10 percent Latinx employees. From there, those targets should increase to 13 percent and 17 percent.

“No one is close to that,” Pao says. “There isn’t a startup that’s actually where it should be. All of them are problematic.”

Discounting Apple and Amazon (both declined to comment for this story) — due to the fact that their numbers are inflated because of their respective retail and warehouse employee populations — the company closest to achieving full representation of black and Latinx employees is Lyft. Lyft is 9 percent Latinx and 10.2 percent black, according to its 2018 diversity numbers.

And since gender is non-binary, at least 5% of a company’s workforce should identify as such and the remaining 45% should identify as female, according to Pao.

But one diversity scandal after another proves a couple of things. One is that there’s still not enough representation. The second is that there are still structural issues in place that create non-inclusive work environments and can fuel imposter syndrome. These structural issues entail things like an inconsistent performance review process, unclear and arbitrary paths to promotion, an ambiguous process for reporting bad behavior and secret conversations known as backchanneling. These private backchannels can create exclusive environments that prevent open, productive conversations.

This is where inclusion efforts — ideally with the buy-in from the CEO — can help. Without true inclusion, any diversity progress made will not last.

“We’re never going to make any progress by adding talent from diverse backgrounds if we don’t fix the inclusion and culture issues,” Kapor Klein says.

Some companies have implemented unconscious bias training, but this initiative alone does not make statistically significant differences, either in reducing the incidence of bias or unfairness or increasing retention, Kapor Klein says.

DETROIT, MI – MAY 05: Lotus 1-2-3 Developer/honoree Mitchell Kapor and wife Founder of the Center for Social Impact and Partner at Kapor Capital/honoree Freada Kapor Klein speak at the 17th Annual Ford Freedom Awards at Max Fischer Music Center on May 5, 2015 in Detroit, Michigan. (Photo by Monica Morgan/WireImage)

“There is increasing serious research pointing out that unconscious bias training, especially as a one-off, is not only ineffective, it can be counterproductive,” she says. “What happens is people say, ‘Ok, I checked that box. I went to one hour of unconscious bias training so that must undo the 29 years I’ve lived on this planet getting biased input every day.’ I think we have to look at not just what’s ineffective but what actually either promotes backlash or is indeed counterproductive.”

This is where heads of diversity and inclusion are theoretically supposed to come in. Unfortunately, they are not always set up to succeed within organizations and can end up becoming companies’ instruments for lip service.

“I don’t know that anyone [a head of D&I] has done it in an impactful way where this person reports into the CEO and has the authority to stop other executives from making really bad decisions related to diversity and inclusion,” Pao says. “Most of them are under the head of HR or people or under legal. They’re not empowered and they don’t have the team or the authority and there’s no metric that they can push people toward and hold people accountable to. They’re in this weird role where a lot of it is external facing.”

Take Google, for example. The company is on its third head of diversity since 2016 and has some of the more outspoken employees who are fed up with Google’s culture.

“Let’s just call it like it is,” Leslie Miley, a former engineering manager at Twitter, Google and Apple, tells TechCrunch. “Google can’t keep a D&I person.”

In April, Google’s chief diversity officer, Danielle Brown, left the company to join payroll and benefits startup Gusto. Google brought Brown on board following Nancy Lee’s exit from the company in 2016. At the time, it was understood that Lee was retiring but has since joined electric scooter startup Lime as its chief human resources officer. Lee, however, tells TechCrunch she was not sure if her retirement would be permanent or not.

“It’s a thankless job,” Miley says. “I think at most companies it’s thankless. Danielle Brown is a really good example of this. You’re criticized by people for not doing enough, criticized by people for trying to do too much. There will always be a fight for resources, accountability. And when you’re at the intersection of gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation, that makes a lot of people fundamentally uncomfortable. And it just wears on you.”

Another issue with this role is that it too often reports to the human resources department, rather than directly to the CEO. With human resources, Miley says, that role is about limiting the liability of the company. So if that’s the department to which a head of diversity and inclusion reports, it’s hard to effect change that is in service of employees.

Lee, who is now in a human resources role, says the effectiveness of a diversity lead who reports to HR depends on the relationship HR has to the rest of the executive team.

“But if you have a company that is particularly lacking in diversity, then maybe there does need to be a D&I person who reports directly to the CEO,” she says.

Monica Poindexter, the newly appointed head of inclusion and diversity at Lyft, reports to Lyft’s VP of Talent and Inclusion but says there is a strong commitment from Lyft co-founders John Zimmer and Logan Green. While she’s confident in Lyft’s approach to diversity and inclusion, as well as some other companies’ individual approaches, she takes issue with the fact that everyone is trying to attack the problem from a multitude of different ways.

“If there was an opportunity to align on one or two tech industry-wide initiatives as it relates to XYZ, then we could have a collective impact,” she tells TechCrunch, “The one thing could be around if we need to evolve the tech interview process and assessing our hiring processes to understand when and how we can improve the opportunities in creating greater pathways for diverse populations.”

Over the years, groups of diversity and inclusion leaders have formed but they haven’t stuck around.

“Quite honestly, there is a lot of change in these roles,” she says. “There might be some momentum at one point but it also depends on how much support that one head of D&I has. The idea of getting them all together — that’s been done — but if we’re really going to influence this, it should be the heads of the tech companies that get together to talk about some of these challenges.”

Candice Morgan, head of inclusion and diversity at Pinterest, has one of the longest stints at any tech company’s diversity and inclusion department. She’s been there since January 2016, “which in tech years, but also D&I years, is a long amount of time,” she tells TechCrunch.

“In the last three years, there have been some major changes in the industry more broadly and in our approach,” she says.

2016 was the first time Pinterest set public hiring goals and was very focused on recruiting, Morgan says. The following year, Pinterest focused a lot more energy around inclusion, and hired an inclusion specialist, increased the amount of employee resource groups and started looking at managers based on employee engagement scores.

“We identified managers that were exceptionally inclusive,” Morgan says. “On the other side, we looked at managers getting average scores around inclusion. We asked ourselves what these inclusive managers were doing differently. They displayed a huge growth mindset, they were more likely to be humble and talk about mistakes and saw failure as opportunities to grow.”

From there, Pinterest built an inclusive management handbook and training based on its learnings. And Pinterest integrated its unconscious bias training into its orientation in 2017.

Despite the common idea that diversity and inclusion leaders have little agency, Morgan seems to have a bit more sway than some of her peers. Morgan attributes that to the relationships she’s built during the amount of time she’s been at Pinterest. In January, for example, Pinterest unveiled more inclusive beauty searches on its platform. As Pinterest stated at the time, the product feature was a result of a collaboration between the company’s technical and D&I teams working together.

“Every single one of us is doing this work,” Morgan says. “We are gaining influence in a number of ways, we’re constantly coaching leaders and so when you start to build those relationships with them, you’re very much a business partner and you can influence them. With the skin tone work, it started as something on the side that we needed to socialize a number of times.”

This year, Morgan says she’s been especially focused on microaggressions, subtle behaviors that can lead to people feeling excluded. They can be anything from commenting on a black person’s hair to using gendered language. Another example, which former Uber engineer Susan Fowler Rigetti pointed to in her damning post about Uber, is only offering company swag in men’s sizes.

As part of Morgan’s work, she’s identifying the “behaviors we can intercept to create micro-affirmations.” Micro-affirmations are small, inclusive behaviors that offer encouragement and validation to others.

“I taught a class with my inclusion program specialist focused on microaggressions and raising awareness around subtle behaviors and how they make people feel,” she says. “There is a tendency for companies or individuals to pat themselves on the back, but what happens there are more subtle ways people can feel excluded or included. I’ve been spending a lot of time creating these roundtables where we put our leaders together.”

For example, she’s had discussions with Pinterest’s head of engineering and underrepresented engineers to discuss what does belonging look like on the engineering team. Every senior engineer, she says, has gone through one of those sessions.

Having a diversity and inclusion leader can surely be effective, and can be most effective if that leader has the ability to effect change and interface with senior leaders — preferably, the CEO. But only two D&I initiatives, Kapor Klein says, can make a difference as standalone. That’s setting specific diversity goals and giving a differential bonus for employee referrals of diverse talent.

“What’s fascinating to me is that those two initiatives require CEO support and also very sophisticated senior management support because both of those initiatives encounter backlash,” she says.

And for either one of those to be effective, there has to be an enlightened senior management team that understands the nuance and can push back when the CTO or a VP of engineering or anyone else says, ‘Wait a second, that’s quote, unquote, reverse discrimination or that’s unfair,’ or however they push that. So to be able to talk about what it means to create a level playing field requires a CEO who has some degree of sophistication and understands the nuance of the issue.”

The data says that “no matter how many bells and whistles you put into place, there is no substitute for an unequivocal commitment from the top,” she says. “Whoever is around that table needs to have a diversity lens when any business issue is being talked about.”

If five key initiatives are in place, however, there can be a significant change, she says. That brings Kapor Klein to her comprehensive approach, which she first outlined more than 10 years ago in “Giving Notice.”

Investing in diverse folks

Another contributor to this overall lack of diversity in tech is the lack of funding that goes to underrepresented founders. Last year, female founders brought in just 2.2 percent of U.S. venture capital dollars. And it surely doesn’t help that less than 10 percent of decision-makers at VC firms in the U.S. are women.

“I want to also share that it’s not just a lack of funding, it’s that women are treated differently,” Women Who Tech founder Allyson Kapin tells TechCrunch.

Kapin points to a survey that Women Who Tech conducted a couple of years ago that found, of the 44 percent of women who reported harassment, 77 percent of them said they experienced sexual harassment as founders. And 65 percent of those sexually harassed reported being propositioned for sex in exchange for funding, Kapin says.

“There is not an even leveled playing field,” Kapin says. “You can have incredible traction, but women-led startups face barriers in terms of how critiqued they are and now you bring in a whole other level of sexism, sexual harassment and grossly propositioning women for sex in exchange for funding.”

Unfortunately, it’s an even starker picture for black female founders. While the number of black women who have received more than $1 million in investment is growing, the number is still small. In 2015, there were 12 black women who had raised more than $1 million in funding, according to digitalundivided’s new ProjectDiane report. In 2017, there were 34.

Still, the median amount of funding raised by black women is $0. That’s because the majority of startups founded by black women receive no money. Of the black women who raised less than $1 million in funding, the average raised amount is $42,000. In total, according to digitalundivided, black women have raised just .0006 percent of all tech venture funding since 2009.

“The founders are leaving VC behind,” Backstage Capital Founding Partner Arlan Hamilton tells TechCrunch. “They tried, they asked, they asked nicely and VCs are not biting. I have a little bit more fuel in me to keep beating this drum of institutional investors and LPs, but it’s very soon going to be leaving them behind at the station, and they’re going to look up and ask, ‘Why wasn’t I in this deal?’ And the same way I was yelling at people four years ago saying black people make companies, the same thing is going to happen here. I’m over them.”

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – SEPTEMBER 05: Backstage Capital Founder and Managing Partner Arlan Hamilton speaks onstage during Day 1 of TechCrunch Disrupt SF 2018 at Moscone Center on September 5, 2018 in San Francisco, California. (Photo by Kimberly White/Getty Images for TechCrunch)

Backstage Capital, which is designed to exclusively invest in black founders, closed its first $5 million fund toward the end of 2016. Hamilton is in the process of closing a second $36 million fund to continue investing in people of color, despite false reports that she had given up.

“There was never a point ever that we stopped raising for the fund,” Hamilton tells TechCrunch. “There was never a point where we thought about stopping. We are in the middle of raising for the fund. It’s taking longer than we hope. The story is why does it take so long to raise a drop in the bucket of a fund. Why are people dropping out? Why are people not stepping up?”

Since its inception, Backstage Capital has invested in more than 60 startups led by underrepresented founders. What initially drove her was the fact that “there were people being overlooked for ridiculous reasons and that oversight was an opportunity.”

“It couldn’t stay that way without something breaking, and something has broken,” she says. “It has broken in a good way — breaking good. You see it almost every day there’s some other announcement about a black or brown founder or LGBT person defying odds.”

Hamilton points to success stories like Jewel Burks, who sold her company Partpic to Amazon, and Morgan DeBaun, whose media company Blavity is objectively killing it.

“This is the proof in the pudding that makes me know today that my instincts are right and what I’m saying comes true,” Hamilton says. “If you saw what happened the last few years, you have to believe there’s something I’m saying today that will come true.”

Within Backstage Capital’s portfolio, Hamilton says we’ll see founders in the next 18 months announce revenue “out of this world” and raise significant rounds. There’s a lot that is very promising to her, despite the lack of support from institutional investors.

There are very few black and Latinx investors, with only 2 percent of investment team members at VC firms identifying as black and just 1 percent identifying as Latinx, according to the National Venture Capital Association.

But there are some other funds cropping up that are run by black women and women of color, Hamilton says. There’s also Lo Toney, formerly of GV, who recently raised $35 million to fund diverse investors via Plexo Capital.

Still, the industry needs more than just a handful of people making a point to fund folks from diverse backgrounds.

“I don’t think institutional [VC] will get their act together fast enough,” Hamilton says.

There’s also an inherent economic privilege that plays into this. The racial wealth gap is vast and it surely impacts some potential founders of color to pursue startups. The median white family in the U.S. has 41 times the amount of wealth than the median black family and 22 times more wealth than the median Latinx family, according to the Institute for Policy Studies.

While white founders may have the support of their wealthy parents or grandparents during the early days, people of color don’t always have that to fall back on. There is some hope, however, with presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren. Last week, Warren called out venture capital for failing diverse founders and unveiled a plan to support founders of color.

Read more: https://techcrunch.com/2019/06/17/the-future-of-diversity-and-inclusion-in-tech/

Recent Comments