My dad was one of the only people with a golden ticket on American Airlines. This is the true story of having and losing a superpower

On 10 March 2009, a case was filed in the US circuit court for the northern district of Illinois, where I grew up. Rothstein v American Airlines, Inc starred my father, Plaintiff Steven Rothstein, and the defendant, then the worlds third-largest airline. With $23bn in annual revenue, American Airlines had nothing to lose. For my father, it was a last-ditch effort to save his life.

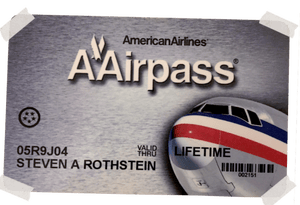

Heres how it all took off. In the early 1980s, American rolled out AAirpass, a prepaid membership program that let very frequent flyers purchase discounted tickets by locking in a certain number of annual miles they presumed they might fly in advance. My 30-something-year-old father, having been a frequent flyer for his entire life, purchased one. Then, a few years later, American introduced something straight out of an avid travelers fantasy: an unlimited ticket.

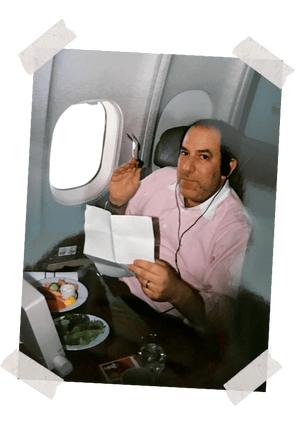

In 1987, amid a lucrative year as a Bear Stearns stockbroker, my father became one of only a few dozen people on earth to purchase an unlimited, lifetime AAirpass. A quarter of a million dollars gave him access to fly first class anywhere in the world on American for the rest of his life. He flew so much it paid for itself. Often hed leave in the morning for a business trip, fly back, and I hadnt even known hed left. Other times, I remember calling his office to find out what country he was in. He (and our whole family) was featured on NBCs Today Show in 2003, and then on MSNBC in 2006. For 20 years, he was one of Americans top fliers, accumulating more than 30 million miles, which he acquired every time he flew, even with the AAirpass.

Then, on 13 December 2008, American took the AAirpass away.

For several years, the revenues department at American had been monitoring my father and other AAirpass holders to see how much their golden tickets were costing the airline in lost revenue. After 20 years, it seems, theyd decided the pass wasnt such a good idea. My father was one of several lifetime, unlimited AAirpass holders American claimed had breached their contracts.

A few months later, my father sued American for breaking their deal, and more importantly, taking away something integral to who he was. The legal fight went on for years without going to trial. The story became front-page news. The Los Angeles Times. The New York Post. Fox News. A slew of online outlets. Its even a perennially popular conversation topic on Reddit.

The obvious story is that my father was a decadent jet-setter who either screwed or got screwed by American; depends on your take. The coverage is always sensational. And I think as does my whole family, including my dad that at the very least, it doesnt quite land.

Legend goes, upon bringing me to OHare Airport as a baby, my father said, This is daddys playground.

Dad has loved to travel for his entire life. His father, Josh, was a navigator in the army air corps during the second world war and ran a company that manufactured paper and artificial flowers, traveling worldwide and telling stories about the places he went.

When I was nine, Dad tells me, we went to Denver. When he left in the morning to go on his business appointments, he said to me: stay at the pool, charge your lunch to the room, and Ill see you at dinnertime. Make sure you have your tie on.

When he was 16, Dads parents took him on a three-and-a-half-week trip: New YorkSan FranciscoHonoluluKamuelaTokyoNagoyaOsakaOkinawaTaipeiHong KongCalcuttaKarachiTehranRomeFlorenceNiceLondonNew York.

I began to taste, directly, the fervor of foreign travel, he tells me. I felt as at home in Copenhagen or Paris as I did in New York I was a child of the world.

He wrote his college application on a typewriter at a hotel beach in Hawaii and mailed it from a post office in Osaka. In college he worked for a travel agency helping students book standby flights at low fares, which he utilized himself. I was on my own and could go anywhere at a moments notice, he reminisces. He flew to Europe several times a year and went to live there after graduating in 1972.

That December, he joined the wallet business a company my grandfather had purchased doing sales. He had an apartment in Manhattan on East 89th Street, but mostly, he was at the wallet factory in Oklahoma, or traveling, both for work and play. On the weekends, hed rush to Houston, Dallas, Wichita Falls, Mexico City or Acapulco, then back to work on Monday.

Steven got on a plane like most people get on a bus, says my mom, Nancy Rothstein, who was married to my father for 36 years.

Transitioning to finance, Dad moved to Chicago in 1976 for a stint at Smith Barney and, according to him, became the second-highest-grossing stockbroker at Bear Stearns in 1979, where he worked for a decade. Later, he focused on investment banking, and also became the largest shareholder of the financial corporation Olympic Cascade, the holding company of a brokerage firm, National Securities. Through it all, he continued flying. Everywhere. Airports and airplanes they were who Dad was.

When American started the AAdvantage program, Dad and Uncle Shelly (Moms uncle and one of Dads best friends and business associates) began flying even more than they already did. Then, after a good year at Bear, the investment in an unlimited pass made sense.

In September 1987, five months after my brother, Josh, was born, and three months after we moved from downtown Chicago into the north suburbs, Dad bought his unlimited lifetime AAirpass. The cost was $250,000, which the agreement stated was based on his age. My father was 37 years and four days old when he dated the check.

Two years later, which was one year before my younger sister, Natalie, was born, he added a companion feature to his AAirpass, allowing him to bring another person along on any flight. The cost was $150,000, based on his being 39 years old. This changed the game, not only for him, but our entire family.

Ernie Thurmond, a former American employee who handled Dads AAirpass contracts, helped with adding some special stipulations. My parents decided early on to take separate planes so that in the unlikely event of a crash, at least one of them would be alive for their three children. So the agreement amendment stated: If spouse is the companion, the spouse will be allowed to travel separately from Holder, provided that the spouse travels on the flight immediately prior to or just after the flight taken by Holder. My parents wouldnt fly on the same plane for at least a decade after that.

Major US and global hubs became Dads office; American became his home. He knew every employee on his journey from the curb, through security, to the gate, and on to the plane.

In the early 1990s, Dad found his go-to agent at the American Airlines Platinum desk: Lorraine Cross from Raleigh, North Carolina. None of us has ever met her in person. But Lorraine was family, her southern lilt a speakerphone staple at the dinner table. While my father befriended dozens and dozens of American employees throughout his tenure as one of their top fliers, no one played a role quite like Lorraine.

Lorraine and Dad became fast pals. Over the next decade-plus, hed send Lorraine and others at Platinum postcards from Maine when he took us to sleepaway camp, menus from restaurants around the world, and magazines from foreign airport lounges. Lorraine loved receiving these; shes even kept the postcards after all these years.

She says they shared inside jokes a lot. Every time I talked to your father, as we would close the conversation Im southern I would always say, Bye now. That was my closing. He would say, Pay later. Caroline, we used to laugh all the time.

Lorraine and the other Platinum desk employees werent his only pals. Recently, Dad described himself as being like an adopted child. American and its employees were his parents. He knew the skycaps at OHare, LaGuardia, JFK, Heathrow, LAX; the people at the front desk at the Admirals Club pre-departure lounges; flight attendants on hauls he frequently flew; the gate attendants; and the folks who drove the carts from security to the gate, like Aamil.

Aamil whose name Ive changed to respect his privacy was a refugee who fled the Bosnian genocide with his family. Dad met Aamil when he was in high school, driving a cart at OHare, and took him under his wing errands and various paid-for-hire tasks. Ultimately, Aamil started coming over for dinner; picked us up at school; became Joshs big brother ears for his dating rendezvous as he entered high school; and was both an employee and a dear, dear friend.

Dad was gracious and kind in a way you dont see in a lot of people, Lorraine says, recollecting the time he helped fly some priests to Italy to see the Vatican, or when Mom called her from the local Gap to use miles to help a sales clerk visit her mother.

Dad gifted the miles and upgrades he accumulated throughout his life both before and during his AAirpass tenure to dozens and dozens of people. Once he upgraded my cantor and his wife to first class from Amsterdam. He regularly let relatives and people in crisis come along in his extra seat. There was the time he took my brothers best friend on his first airplane ever to see a football game; the American Airlines employee he saw in India, crying because she might lose her job if she didnt make it to Toronto; his brother and sister-in-law for their honeymoon; a guy from college and his wife who really wanted to go to Australia; a man in the back office at National Securities, who wanted to visit his dying father (he got there just in time).

Your familys heart is as big as the state of Texas, Lorraine says. Its incredible how many lives they touched and how many lives touched them because theyre very sensitive and attuned to what goes on in the world.

Im not saying Dad was a saint. Just that his AAirpass was about more than solipsistic travel. It allowed him to build relationships. And it allowed other people to access the world like he did. Thats what Dads AAirpass and ultra-elite flying status yielded for him: lifelong bonds.

On 13 January 1998, the American Airlines CEO, Robert Crandall, wrote my father a letter after theyd seen each other on the Concorde (a transatlantic supersonic aircraft).

At the end, Crandall wrote: I am delighted that youve enjoyed your AAirpass investment you can count on us to keep the Company solid, and to honor the deal, far into the future.

My friend Phil likes to say my father ran his life like a corporation and raised me in it. His underwear was pressed. UPS and FedEx came nightly to our driveway to drop things off, pick things up. He had packing down to a science sets of clothes folded and fitted into plastic cases, cosmetics ready to go. We had a whole suitcase closet in the basement, and at some point, he turned the downstairs guest room into a staging area for packing.

They sort of broke the mold when they made him, says Mom, who is a sleep consultant.

He stored everything he collected while traveling in the basement hotel soaps, shampoos, conditioners; his thickened old passports; towels; shirts; hairdryers and combs from around the world in what we called his Secret Room, the key hidden in his office desk. A fun party trick was bringing people inside his business associates, my siblings and my friends. Sometimes we used the items ourselves. Often, we gave things away. After Hurricane Katrina, Dad and I flew down to New Orleans with boxes of clothes and toiletries. When he went to India, he brought things along. Like travel, for Dad, the Secret Room was an extension of souvenir collecting as a kid.

As a kid myself, I often complained about Dads excessive traveling. I used words like abandonment and neglect. In retrospect, that was wildly dramatic. But its how I felt.

No matter where Steven went, there wasnt a day we didnt talk, Mom says. Some men are home every night at 5.30 from the office, but theyre not really there. Steven Rothstein was there. She emphasizes there with a deep, grinding grunt. Whether he was in the house or out of the house, he was very involved. He was very much there. And always in touch. I mean, he used a phone he was one of the first people with a cellphone.

Shes right. Most of my life, I focused on how Dad was always on a plane. When I think about it now, when he was home, he was there: sitting with me on my bedroom floor, or at the dinner table, or coming in to kiss me goodnight. He has a presence. Not only a loud voice, but also a boom of self. He arrives. He is both taking off and landing at once.

He never missed an opportunity to come home to the family, Lorraine says. I dont care where he was going. I dont care what he was doing. If there was a chance he could come home and stay with his family overnight, he preferred that to any hotel in the world.

I really valued and appreciated that from him, she says. His family meant the most. I would say, Thats a long way to go, are you gonna overnight and come back the next day? Hed go, No, I wanna sleep in my own bed. I wanna go home. I wanna be with my family.

I laugh, tears in my eyes. I didnt know this.

That was crucial to him, to be with his family, Lorraine says. He did some crazy stuff to make that happen over the years.

Dad was an airport celebrity, and when we traveled together, it embarrassed the shit out of me. Like riding a cart from security to the gate (because as a family, we ran late Dad has a knack for rushed arrivals). I would bow my head so I couldnt make eye contact with anyone we passed. Or walking into the Admirals Club locations and having the folks at the front desk know us by name.

Or when, in second grade, he took me to Japan for the weekend because he wanted me to experience an inaugural flight (San Jose to Tokyo). We were in the bulkhead, the first row of any flight cabin. As we landed, there were reporters flooding the jet bridge to photograph the first person off the flight. Technically, based on his seat, that was Dad. But as he figured out what was happening, he insisted I go first so I could be the star. I stood there with my seven-year-old smile, bright-colored headband, and long V-neck Limited Too sweater hanging down to my thighs.

I was mortified. But Dad wanted us to experience absolutely everything there was in life.

He wanted to take me to all 50 states by the time I was 11. We put a big US map on the wall behind his home office desk. After each trip, Id add a pin to the visited state; another for the places I wanted to go. When wed gone to 30-something states, I asked to stop; I wanted to be able to have new adventures as an adult.

You grew up with a different lens than most people you knew, Mom says. Im not saying that other people didnt travel all over the world. But I sort of doubt, for the most part, they had the kind of wanderlust and open-mindedness and fascination that your father had with the world, and still does, for that matter.

I think its a beautiful thing, she says. I remember saying, at some times to Steven are we taking away [their] future experiences by showing you so much so young? But looking back, if it were [me], Id much rather have had this global exposure as a child than waiting until I was an adult. Wouldnt you say it framed you?

Yes, I answer.

Not only framed you, she adds, but it helped with your, your tapestry. It was woven into your tapestry. Into the fabric of who you are, and how you look at other people and the world.

I understood the weight and privilege as a kid. I understood we all did that the AAirpass meant my father could travel and do business in unprecedented ways, and it allowed our entire family to travel in ways few people on earth could. We got the privileges, all of them, all of us.

I ask my sister, Natalie, a psychotherapist living in Chicago, her earliest memories of traveling on an airplane: landing in Australia at age three, walking down the aisle as the plane was still moving, and someone grabbing her to keep her safe. I think I remember that because it was really dramatic, she says. I have a lot of vivid memories from that trip, actually.

Were you aware that we were in first class? I ask.

I didnt sit out of first class until I was 12 years old, she says. I dont know if I was aware when I was three years old. But I was aware very early.

Wont to interrogate privilege race, class and otherwise I pry. Did she really get that first class was different than the rest of the plane?

For a long time, I really wanted to sit in coach, she says, because I felt uncomfortable being a kid in first class when it was clearly where all fancy adults were sitting. It was clear I was surrounded by mostly people who had a lot of money, and I was always one of the only kids in first class, and that felt weird and I always wanted to be with other kids in coach.

That trip to Australia (I was in fifth grade) was our first big international family vacation. The following year, Dad, on a whim, said to Mom: lets go to Tokyo.

Japan! she said. Over Christmas? Are you kidding?

But we went.

Mom can still perfectly picture us all at dusk in Tokyo: Dad has on his camel coat. You and Josh are in all the black-and-white-check stuff. Were walking through an aisle of stalls going to yet another monastery or shrine and the flavors that we felt and saw and tasted it was probably one of the best Christmas vacations wed ever had because we were the only people in the hotel. She starts chuckling. And it was so much fun. It was so unusual to be Americans at Christmas in Tokyo.

It was about seeing the world We wanted to connect to the people, she says. As she recounts these stories, her tone is somewhere between euphoric and frenzied. She punctuates each story with an oh my God and transitions immediately into the next.

When we were in India we got so friendly with our cab driver that we brought him for dinner to the hotel For a while we were in touch We would send him pictures and things. That was the kind of richness that this AAirpass, this sense of a family traveling anywhere we wanted to go in the world that American could take us thats what we did. People enriched us. Hopefully we enriched others.

She starts laughing as she recalls a time we visited the Holy Sepulchre in Israel and Dad got in trouble for lying down with his yoga strap, trying to stretch his back in front of the church. I mean, there was so much color in what we did and where we went and how we did it. The travel was first class, the hotels were first class, but the experiences were very real and authentic. And then without skipping a beat, she goes up an octave with: Oh my God so Josh was dead when we first went to India, right?

Josh was dead both times we went to India, I say.

Yeah, she says. But he was very much with us, Im sure.

On 6 October 2002, Josh 15 and a half was hit by a car while walking down the sidewalk. The car had pulled an illegal U-turn. To avoid a collision, another driver accidentally accelerated, swerved up on to the sidewalk and flung Josh into the side of a building. His head hit the building. He was knocked unconscious. My uncle Jeffrey called me from Scarsdale and told me to get on a plane. It was my first month of college; I rushed to the Philadelphia airport and bought a ticket home. I landed at OHare, descended to baggage claim, into more uncles arms. Their faces distraught: It doesnt look good. It would be at least another 15 years before I could descend the American Airlines baggage claim escalator without going into a trauma shock.

Josh died the next morning our rabbi and the hospital chaplain reciting the end of life Hebrew blessings and prayers; Dad, Natalie, our maternal grandmother, and me standing around the bed; Moms own body draped alongside her dying son; Natalies hand on his heart for his last beat.

Recent Comments