It once felt impious just to mention Auschwitz. Now, 75 years after its liberation, the death camp has spawned a literary subgenre and Hitler is in Oscar-nominated comedy Jojo Rabbit. Are we betraying the dead?

Silence is the angel with which literature wrestles. The silence of inadequacy to the task of expression TS Eliots struggle against last years words while next years words await another voice. The silence of moral hesitancy or humane consideration. The silence enjoined by laws of blasphemy, or fears of persecution. The silence of bad conscience or exhaustion. The silence of tact.

Over and above these, the Holocaust for many writers and thinkers made reticence not a matter of choice but a moral and psychological obligation. No poetry after Auschwitz the philosopher Theodor Adornos famous phrase, ringing through the deathly quiet like the plague bell, could be read both as an injunction and a lament.

Either way, it didnt simply mean no fancy language. It meant not rushing to possess by articulation, or even to explain what might have been beyond explanation, while the thing itself was still warm and its consequences still unfolding. The issue wasnt languages ineffectualness in the face of a terrible event. The Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld, who as a boy was transported to a labour camp and later spent three years foraging and in hiding, wrote of learning silence as a mode of forgetting, burying the bitter memories deep in the bedrock of the soul, in a place where no strangers eye, not even our own, could get to them.

We think of understanding as our greatest gift, and language as our greatest means of expressing it, but it was Primo Levi author of If This Is a Man, the finest of all accounts of life in the camps who warned against understanding the Nazi project to eliminate the Jews, as though it were susceptible to rationality. It might be that the deep bedrock of the soul is a better place to house what defeats reason than the printed page or the cinema screen.

For many who survived incarceration and torture, Appelfelds silence became a way of being, without consolation or salve. The idea of cure, let alone transfiguration, belongs to a later generation of Holocaust excavators, those who had not experienced for themselves but wanted to speak as though they had, either to berate those they felt hadnt learned its lessons or simply to profit from it in some way peddling kitsch being the most profitable.

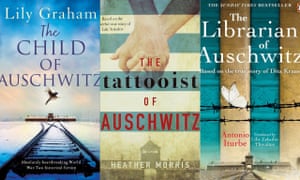

Once it felt impious just to say the word Auschwitz. The clutch of cruel consonants caught in ones throat. Now, as we reach the 75th anniversary of its liberation on 27 January, the horror associated with those consonants has dissolved into an almost jaunty familiarity. Auschwitz today is a tourist destination, whether you mean to go there by train and come back with a trinket or travel to it between the covers of a book. It has even spawned a popular subgenre the Auschwitz novel. Auschwitz Lullaby, The Child of Auschwitz, The Librarian of Auschwitz, The Druggist of Auschwitz, The Tattooist of Auschwitz, The Chiropodist of Auschwitz. Only one of those is made up by me, and whos to say it isnt being written this minute?

Look at the publicity for these novels and you discover the same claim being made for all of them. The Druggist of Auschwitz is a documentary novel. The Child of Auschwitz is described as historical fiction. The Librarian of Auschwitz is based on an incredible true story. As for the latest, The Tattooist of Auschwitz, it is the real-life story of how a Slovakian Jew fell in love with a girl he was tattooing in the camp. In other words, they are all novels that are not prepared to take the risk of being works of the imagination, and therefore exist in some no mans land between fact and fancy.

How we feel about novels making claims to be true, over and above what we mean by imaginatively true, will tell us how we feel about novels altogether. It isnt new for writers or their publishers to make such declarations. Daniel Defoes Robinson Crusoe was sold on the assurance that his Life and strange surprizing adventures were written by himself and therefore authentic. Moll Flanders the same. And that was 300 years ago. But the novel has evolved considerably since then and it hasnt been thought necessary to assure us that Thomas Hardy based Jude the Obscure on a real Dorsetshire loser who wasnt able to kill a pig. That we are returning to fact to justify fiction is the sure sign that the novel no longer commands the respect it did.

Only when a story avowedly tells of something that really happened, it seems, are we willing to grace it with our credulity and tears. Ironically, a number of these works have been criticised by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum for failing to live up to their own promises of authenticity. Heather Morriss The Tattooist of Auschwitz, the Memorial complains, contains numerous errors and information inconsistent with the facts, as well as exaggerations, misinterpretations and understatements.

The publishers response Heather is a fiction writer, not a historian is a disingenuous attempt to have it both ways. Either youre aiming to tell the historical truth or you arent. The classic defence of novels and films of this sort, that they are based on real events, is no defence at all. Based conceals a world of subterfuge, giving the author access to the best of both worlds truth in the historical sense and truth in the imaginative while having to bear responsibility for neither.

The question we have to ask is why readers are so eager to enter into this shady contract. What is it about historical truth that licenses them to be moved in a way that imaginative truth no longer seems to? The Tattooist of Auschwitz fulfils two of the classic expectations of kitsch. By sweetening the horrors of the camps (I tattooed a number on her arm. She tattooed her name on my heart) it answers to Milan Kunderas claim that kitsch is the absolute denial of shit. And in its faux historicism right down to the inclusion of photographs of the actual tattooist whose story the novel borrows it angles for those double tears that are the hallmark of kitsch: weeping over the suffering of others and weeping a second time over our capacity to do so.

To be clear: it is not my argument that the Holocaust should be approached as though it is the Holy of Holies. I have been chased from the Temple myself, accused of defacing sacred memory in my novel Kalooki Nights by detailing the adolescent heros obsession with Ilse Koch, the notoriously sadistic wife of the commandant of Buchenwald. An early copy of Lord Russell of Liverpools The Scourge of the Swastika, complete with grainy, semi-sadomasochistic photographs, falls into the boys hands when he is of an age to be susceptible to its imagery. Thereafter, his imagination riots in the hell of Buchenwald.

But there is all the difference in the world between pornographic exploitation of the Holocaust and a dramatisation of how reading about it can be deranging. The forms in which we receive and process images of the camps are integral now to what the Holocaust means to us. There is nothing titillating about their study.

Nor is there blasphemy in disturbing the solemn hush with parody and satire. If we are to know and bear witness while accepting Levis injunction against understanding, we need all our wits about us. Sometimes the comedy just isnt comic enough, as is the case in Charlie Chaplins The Great Dictator; or not funny at all as in Roberto Benignis film Life Is Beautiful; and sometimes it makes us squirm and fret, and then wonder why we shouldnt, as in Martin Amiss novel The Zone of Interest. But comedy can be a contentious and disruptive force whether or not its subject is the Holocaust. The important thing is to accept that seriousness can take many forms.

Taika Waititis Jojo Rabbit has several Oscar nominations, including for best film (warning: spoiler details ahead). It tells of a 10-year-old German boy living at the end of the second world war, who moves from being a member of the Hitler Youth to helping conceal a Jewish girl in his house. To complicate his loyalties, his imaginary friend is the Fhrer, played farcically by Waititi himself. In a gesture that might be said to complete his de-Nazification, Jojo finally shouts, Fuck off, Hitler, and kicks him out of the window. Is this too cute to be cathartic? Kitsch is a parody of catharsis, Adorno wrote. Could Jojo Rabbits breezy optimism be deceptive? Could it be concealing a parody of kitsch?

Whatever the film is up to, it cant be accused of spurious reverence. An atrocious event doesnt automatically confer seriousness on every representation of it. Seriousness has to be earned again each time. A feelgood Holocaust whether it takes the form of pseudo-historicity or redemption romance not only exploits the dead, it demeans the living.

I am afraid of one thing, Dostoevsky said. That I wont be worthy of my torment. We who never experienced the torments of the Holocaust for ourselves bear a double responsibility: first to those who did and then to our own capacity to imagine without false solace. Silence was once thought to be the only way to penetrate this darkest of dark places. Now we are talking again, we owe it to humanity not to belittle or betray the deep bedrock of the soul.

Recent Comments