Image copyright Charles McQuillan

Image copyright Charles McQuillan Corrupt or malicious activity was not the cause of what went wrong with Northern Ireland’s failed energy scheme.

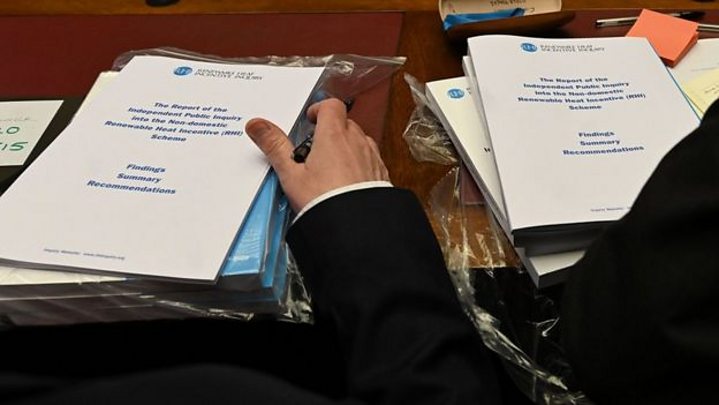

The findings into the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme were published on Friday.

It found the scheme was a “project too far” for the NI Executive and “should never have been adopted”.

The scheme, which opened in 2012, paid businesses to switch from oil and gas to environmentally-friendly heating.

The 656-page report said that while there was “unacceptable” behaviour by some officials, ministers and special advisers, what went wrong was a “compounding of errors and omissions over time and a failure of attention”.

Set up to encourage the use of renewable energy sources, the RHI closed to new entrants in 2016 amid concerns about the potential cost.

Those boilers used wood pellets, but the subsidy payment was higher than the cost of the fuel, creating an incentive to use the boilers to generate income.

It became known as “cash for ash”.

Arlene Foster ‘sorry for failings’

The scheme was introduced by then Enterprise Minister Arlene Foster.

Following the report’s publication, Mrs Foster, now the first minister, repeated an apology for her “failings in the implementation” of the RHI scheme.

She added that she is “determined to learn from my mistakes and to work to ensure that the mistakes and systematic failures of the past are not repeated”.

Finance Minister Conor Murphy said it was now the responsibility of the executive to “put (the report’s) recommendations into action to change the system”.

“We need effective government and we need good practice in terms of our handling of public finances and we need to ensure that an issue such as this… can never arise again,” the Sinn Féin MLA said.

Mrs Foster had told the inquiry that she did not read the regulations before bringing them to the assembly.

The inquiry found: “The minister, in presenting the regulations to the assembly and asking for their approval, should have read them herself.

“Not least because in the inquiry’s view to so do is a core part of a minister’s job.”

However, it has found that as enterprise minister, Mrs Foster was given inaccurate and misleading information.

- The RHI report: In full

- Live updates: RHI Inquiry report publication

- Latest reaction to the RHI report

The report also criticises the arrangement between Mrs Foster and her special advisor (Spad) Andrew Crawford.

It said the division of responsibility between them for reading and digesting important documents was “ineffective and led to false reassurance on the part of the minister”.

The Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS), and in particular the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI), have come under heavy criticism.

The report finds that at the development stage “insufficient care was taken within DETI to weigh properly the whole-life costs” of the scheme.

A draft regulatory impact assessment presented to Mrs Foster in 2012 “lacked necessary cost information”.

The report noted that at this point she had already been “incorrectly” told by officials that the scheme provided “the highest renewable heat output at the best value”.

The lack of record keeping was also highlighted.

It emerged during the inquiry that many meetings had not been minuted by civil servants.

“Basic administration and record keeping, normally the bedrock of the Civil Service, was on too many occasions lacking within DETI,” it said.

“This contributed to uncertainty as to what discussions had actually taken place.”

What was the RHI scandal?

The RHI scheme paid 1,200 businesses to switch from oil and gas to what was meant to be environmentally-friendly heating, using wood pellet boilers. Some businesses put in multiple boilers.

But the subsidy payment was higher than the cost of the fuel, creating an incentive to use the boilers to generate income.

It became known as “cash for ash” and a lack of cost controls meant it threatened a massive overspend on the Stormont budget.

The financial scandal led to the collapse of Northern Ireland’s political institutions in 2017 and caused a three-year political stalemate. The political institutions were only reinstated in January 2020.

A public inquiry into the scheme was set up in 2017. It took evidence from high-profile politicians, civil servants and consultants who designed the scheme as well as administrators who ran it.

No expertise or support

Further criticism of the NICS said that having embarked on the RHI scheme, DETI did not ensure that “adequate resources and expertise were applied to its development”.

“Those junior civil servants responsible for the scheme day-to-day, no matter how hardworking and well-intentioned, were consistently under resourced.

“They were not equipped with the necessary expertise, nor adequately supported.”

A “wholesale and uncoordinated changeover of staff” who had knowledge of the scheme within DETI should not have been allowed to happen between 2013 and 2014.

In 2015, when problems were recognised, the actions of senior civil servants were not good enough to ensure they were identified and addressed.

The inquiry also found that the whistleblower who repeatedly contacted DETI with her concerns should have been treated better.

Image copyright Pacemaker

Image copyright Pacemaker Janette O’Hagan repeatedly contacted DETI between 2013 and 2015 to highlight abuse of the scheme, but her warnings were overlooked.

The report said her treatment “fell well below the standard she was entitled to expect”.

It also said there were “instances of unacceptable behaviour by Spads”, highlighting one who shared confidential government documents, not just about RHI, with family members.

Another instance involved a number of Spads and a minister, discussing a plan to disclose information to divert media attention away from their party.

Inadequate governance

The “unsatisfactory” relationship between DETI and Ofgem, the scheme’s administrator, was also highlighted.

The service Ofgem provided to the department “fell below that standard that DETI could reasonably have expected”.

The report said Ofgem had relevant information about scheme exploitation and did not pass this information on.

This failure of communication “deprived DETI of important opportunities to be confronted with or reminded of the problems of the scheme”.

Ultimately the report finds that “responsibility for what went wrong lay not just with one individual or group but with a broad range or persons and organisations involved”.

“There were repeated missed opportunities to identify and correct, to seek or have others correct, the flaws in the scheme.

“The sad reality is, that in addition to a significant number of individual shortcomings, the very governance, management and communication systems, which in these circumstances should have provided early warning of impending problems and fail safes against such problems, proved inadequate.”

Read more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-51840287

Recent Comments