The long read: Amid the convulsions in the years following the Arab Spring, Peter Hessler went to the ancient city of Amarna, site of another short-lived attempt to remake a nation

They say there is something special about buying your first brand-new car, and this is particularly true if it happens in Egypt during a revolution. By the spring of 2014, my wife, Leslie, and I had lived in Cairo for more than two years, as American foreign correspondents, and we had reached a point of decision. The previous summer, Mohamed Morsi, the countrys first democratically elected president, had been removed in a military coup, and the security forces massacred more than 1,000 Morsi supporters in the capital, according to estimates by Human Rights Watch. At the time, our twin daughters, Ariel and Natasha, were three years old, and Leslie and I had the inevitable conversation: do we stay or do we go?

We had always intended to spend at least five years in Egypt. It seemed the minimum, given the richness of the countrys history and culture, and in the end we decided to stick to the plan. Purchasing the first new car that either of us had ever owned was part of that commitment an act of determination, or maybe desperation.

Initially, the normalcy of this routine seemed reassuring. At a dealership in eastern Cairo, a salesman in a dark suit gave us a firm handshake and a good price on a Honda City sedan. After that, we scheduled a meeting with an agent at the insurance company Allianz but, at the last minute, he called to cancel, because he had just destroyed his own car in an accident. Another agent stepped in. She mentioned that she no longer qualified for auto insurance from Allianz, because she had had multiple wrecks every year for three consecutive years. She handed us a glossy brochure that read: Our own data shows that six out of every 10 cars purchased in Egypt will either be crashed, damaged, or stolen.

By the time we finished the paperwork, I was so scared that I telephoned a car-owning friend. He drove over and guided me through rush-hour traffic, like a tugboat, to our home in Zamalek, a district on an island in the Nile. But it wasnt long before I started exploring the city, and then I discovered the joy of driving to ancient sites. Even at the most imposing monuments, there was something intimate about the experience, because these places had been abandoned by tourists. When we made a family trip to the Red Pyramid at Dahshur, I parked the Honda City at the base of the structure, as if we had pulled up at a friends house. There wasnt another vehicle in the car park; the guard at the entrance was so bored that he didnt bother to accompany us inside. We descended alone into the pharaohs burial chamber, where the twins voices echoed off the high corbelled ceiling.

For a couple of years, I had researched archaeological digs in Upper Egypt, and now I made trips alone in the car. The hardest part of every journey was escaping Cairo. From Zamalek, I would head south along the Nile, past Tahrir Square and Garden City, the old district of the British colonialists. Then I reached Fustat, where, more than 1,000 years ago, Arab invaders founded the capital that eventually grew to become Cairo. The distance was only three-and-a-half miles; on a bad day it took an hour.

Whenever the traffic bogged down, I read the cars around me. Egyptians liked to post statements in white decal letters on their rear windows, and usually they were the standards: mashaallah (this is what God has willed) or la ilaha illallah (there is no God but God). But sometimes, a message had been designed for those godless moments when nothing moved. Mafeesh faida (Theres no use). Ana Taben (Im Tired). The most memorable were often in English: Real Women Hunt. Love Story Jesus. If Your Life Is a Minute, Live It as a Man. A Kia Cerato had Try but Dont Cry on its back window. A Jumbo-brand bus had Thats What Friendship Leads to, a Court Case. A Lada sedan: Police Is My Job, Crime Is My Game.

South of the city, I passed the high walls of the notorious Tora prison, and from there it wasnt far to the Cairo-Asyut desert highway. At the tollbooth, I paid the equivalent of about 1.50, the best money I ever spent in Egypt. To the east rose low flat mountains of brown and red. The highway skirted the lower flanks, and soon the hazy green of the river valley disappeared in the west.

High on the desert plateau, the road surface was excellent, and there were hardly any other cars. It never rained; the light couldnt have been better. Thanks to government subsidies, gasoline was cheaper than bottled water. On some sections of road I drove for 50 miles without seeing any vegetation.

At 75mph, with air-conditioning, it was hard to imagine the desert journeys of old. In 1868, an Englishman named Edward Henry Palmer wrote in his diary: Monday walked six hours; saw two beetles and a crow. Annie Quibell wrote in 1925: It is not the heat, not the glare, nor the sandstorms, nor even the solitude, that become oppressive after a time; it is the utter deadness and the howling of the wind.

For past travellers, the landscape was brutal, but desert solitude often clarified the mind. There is something grand and sublime in the silence and loneliness of these burning plains, Robert Curzon wrote in 1833. A century later, Robin Fedden compared the view to the cleanliness of a country under snow. Arthur Weigall, who excavated at archaeological sites in the early 20th century, wrote: The desert is the breathing-space of the world, and therefore one truly breathes and lives.

Such reactions were by no means limited to foreigners. In the late third century, after Christianity had swept across Egypt, there were two famous instances in which a wealthy young Egyptian left his comfortable Nile valley home for a life of prayer and loneliness in the desert. According to tradition, Paul became the first Christian hermit, and Anthony the first monk. In this narrow river valley, neither man had to travel far to reach a site of desolation. And their relative accessibility allowed for occasional visitors, who informed the rest of Christendom about these holy men. The Egyptian desert that breathing space of the world inspired the Christian tradition of monasticism.

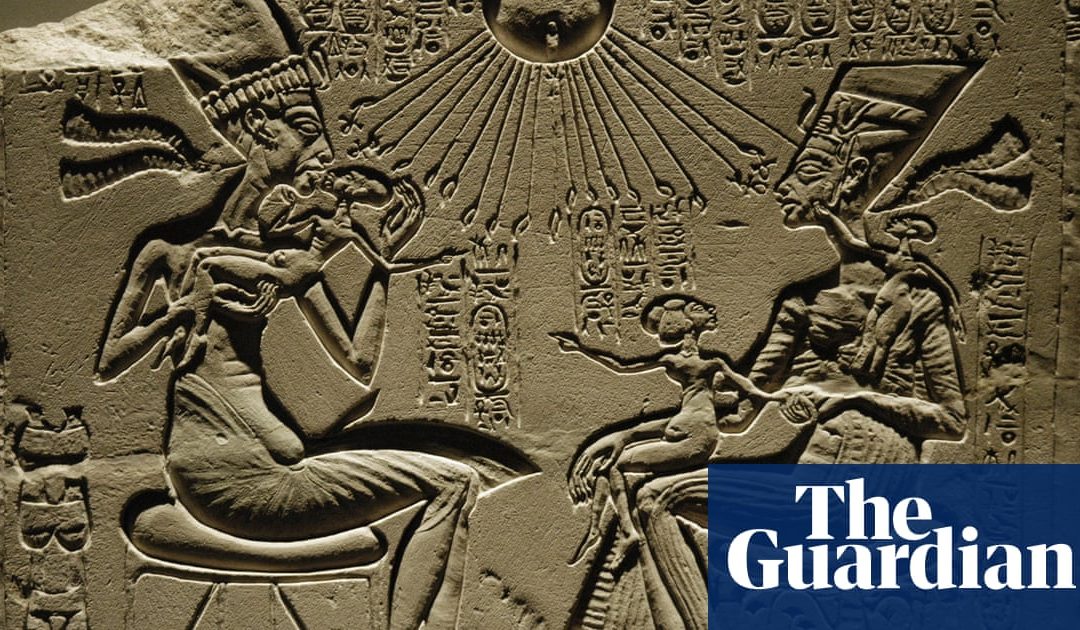

About 1346 BC, in Upper Egypt, the pharaoh Akhenaten founded a new capital on a previously uninhabited shelf of desert above the rivers eastern bank. Major cities had always been situated in the river valley, and when kings built mortuary temples and monuments, they favoured desert sites that were already sanctified by graves of the ancients. But the young pharaoh wanted a landscape uncontaminated by history or ritual. He erected a stele that described his discovery of the site when it did not belong to any god, nor to a goddess, when it did not belong to any male ruler, nor any female ruler, when it did not belong to any people to do their business with it.

By that time, the Egyptian faith had changed remarkably little for nearly a millennium, despite the lack of a central religious text no Quran, no Bible, no Tanakh. It says much about the unchanging rhythm of life in the Nile valley, writes the Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson, dictated by the annual regime of the river itself, that the resulting belief system remained so stable for so long. In a landscape of such simplicity and continuity, core beliefs didnt have to be written down. The Nile was the book.

But Akhenaten wanted a home in the desert, and he wanted a key text. His long poem, now known as the Hymn to the Aten, celebrated the form of the god Ra that was called Aten the disk of the sun. In all respects these words were revolutionary. They were written in a more colloquial language than traditional Egyptian texts, and they celebrated the natural world:

The entire land performs its work; all the flocks are content with their fodder, trees and plants grow, birds fly up to their nests.

The Hymn to the Aten has some parallels in imagery and concept to Psalm 104, and a number of scholars have theorised that the Israelite psalmists might have been influenced by Akhenatens poem. Most strikingly, the hymn emphasised the Aten alone. For the first time in recorded history, an individual took a step toward monotheism:

Sole god, without another beside you; you create the earth as you wish.

Within a few years, Akhenatens desert city became home to an estimated 30,000 people. Palaces, temples and government buildings were constructed at an astonishing pace. The scale was massive; one place of worship, the Great Aten Temple, was half a mile long. So many workshops produced crafts for the royal family that it resembled a factory town. It is an overwhelming site to deal with, wrote William Flinders Petrie, who, in the 1890s, excavated at the place that archaeologists came to call Amarna. Imagine setting about exploring the ruins of Brighton, for that is about the size of the town.

Akhenatens great hymn, and his other texts that described the sites boundaries, failed to mention one key detail: there was no potable water. Crops couldnt grow here. Traditional supply chains had never served this place. The Egyptologist Barry Kemp believes that local well water would have been too saline for drinking, and that residents were forced to haul water from the Nile. Kemp writes: The danger of being an absolute ruler is that no one dares tell you that what you have just decreed is not a good idea.

During one of my drives to Amarna, I pulled over at the site of the Great Aten Temple just after Kemp had found a piece of a broken statue of Akhenaten. Kemps crew was excavating the temples front section, where the fragment poked up through the sandy soil. When Kemp handed it to me, the object felt heavier than I expected granite. It featured the kings lower legs and, around the knee, the figure had been struck with enough force to cause a sheer break. This is not accidentally damaged, Kemp said.

Kemp was in his mid-70s and had worked at Amarna since 1977. From the beginning, he had been drawn to the idea of a city in the desert. Theres a long history of fascination with the figure of Akhenaten, and Egyptologists have traditionally focused on royals and other elites. But at the time of Kemps student years at the University of Liverpool, the field of archaeology was changing, with a new emphasis on the tracings of everyday life. Amarna was the perfect site for such an endeavour. The city was occupied for 12 years at the most, and then, not long after the death of Akhenaten about 1336 BC, it was abandoned completely. Nobody came after the king for the same reason that nobody had preceded him: no water.

When Kemp started excavating at the site, he was a professor at Cambridge University. Eventually, he retired from academia in order to work more often in the field, where he was funded by private donations to the Amarna Project, which he had established. Over decades, he meticulously excavated sections of the city, hoping that small relics of everyday life would answer larger questions. How had the capital been laid out? How was it planned? What did the streets, homes and public buildings say about ancient Egypt?

Kemp was tall and softly spoken, with a full white beard that helped protect against the Amarna sun. He lived for much of the winter and spring in the no-frills dig house that was located on the southern edge of the site. He had spent more than three times as many years digging through the city as Akhenaten had spent building it.

Even after all that time, Kemp was surprised by some discovery almost every season. He had recently determined that the Great Aten temple was completely demolished and rebuilt around the 12th year of Akhenatens reign. This was what had happened to the statue of the king with the broken legs workmen must have smashed the figure and used the pieces as hardcore, or filler, in the new structures foundation. Akhenaten frequently changed his mind about how he wanted to be portrayed, and apparently he had decided that this piece of statuary, like the entire temple, no longer matched his vision.

This is beautifully finished, Kemp said, tracing the lines of the smashed statue. Its an odd thing for them to have done, from our perspective. The statue is no longer needed, so they reduce it to hardcore. He turned the piece of stone over in his hands. We have no commentary on whats going on.

Ancient Egyptians rarely explained themselves. They never identified why they built in the shape of the pyramid, or what those monuments symbolised. We dont know how they moved two-tonne blocks of stone to a height of more than 120 metres. Even basic social traditions remain a mystery. Illustrations on tomb walls provide rich details about funerary practices, but we lack an equivalent source for weddings. In 3,000 years of Egyptian history, there is no direct evidence that any marriage ceremony ever took place.

In ancient Greece and Rome, people left many contemporary commentaries about political and social events. Theres none of that in ancient Egypt, Kemp said. You have to infer a great deal. And you infer with parallels in mind that you have picked up from more recent periods. It becomes difficult to tell how much support somebody like Akhenaten had. Was he totally unpopular? Or was he popular and the military removed all traces of that support?

Without many sources, one inevitably excavates the imagination. In 1905, the Egyptologist James Henry Breasted described Akhenaten as the first individual in human history, because the king stands out so brilliantly against the patterned past. Over the course of the 20th century, the ancient king was portrayed variously as a proto-Christian, a peace-loving environmentalist, an out-and-proud homosexual and a totalitarian dictator. His image was embraced with equal enthusiasm by both the Nazis and the Afrocentric movement. The Nazis connected the Aten to the Aryan tradition of sun worship, and they even convinced themselves that Akhenaten was partly of Aryan descent. In turn, black thinkers celebrated the king as Blackhenaten, a symbol of African power and genius. Thomas Mann, Naguib Mahfouz, Frida Kahlo and Philip Glass all incorporated Akhenaten into their creative work. Sigmund Freud was so excited by Amarna digs during the 1930s that he wrote: If I were a millionaire, I would finance the continuation of these excavations.

Dominic Montserrat, the author of Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt, noted that the king has become a sign rather than a person. But there is enough evidence for a more grounded view of this figure. He was part of the 18th dynasty, which rose to power in conflict with the Hyksos, a group from the eastern Mediterranean that gained control of the delta during the time now known as the Second Intermediate Period. In order to drive out the Hyksos and reconsolidate the empire, the forefathers of the 18th dynasty had to adopt key innovations from their enemy, including the horse-drawn chariot and the composite bow.

This struggle also motivated the 18th dynasty, which began in the mid-16th century BC, to become the first ruling period with a standing army. Eventually, their military control extended from current-day Sudan to Syria, but even as the empire grew, the kings tightened their definition of family. They refused to allow their daughters to marry outside the clan, as a way of consolidating wealth and power. Kings often wedded their daughters, and brothers married sisters. Occasionally, a branch of the family tree ran straight for generations without a fork. The pharaoh Amenhotep I married his sister, and between them they had two parents, two grandparents and two great-grandparents: three generations of sibling marriage. Unsurprisingly, and probably for the greater good of Egypt, Amenhotep I and his sister-queen died without issue.

Despite such genetic pitfalls, the dynasty was brilliant at politics, and it produced many ambitious figures. One such striver was Thutmose IV, Akhenatens grandfather. Thutmose IV wasnt in line for the throne, which he might have seized by having his brother killed. As usual, we have no outside commentary. Thutmose IV himself told a story about falling asleep in the shadow of the Great Sphinx, which at that time was already ancient. He claimed that while he slept, the god Haremakhet visited him in a dream, declaring: I shall give to you the kingship. After the prince became king, he had the dream-story inscribed onto a stele and placed between the Sphinxs paws.

This shrewd political strategy using the past to justify acts of change, disruption or even radicalism was also applied by Thutmose IVs descendants. His son Amenhotep III ruled during a period of unprecedented prosperity and built more monuments than any previous pharaoh. He sent officials to study ancient tombs and temples on the Giza plateau, and began to elevate the Aten, which had been more prominent centuries earlier. The style of court art also began to change in ways that we would describe as more naturalistic. With Akhenaten, these changes became a full-blown movement a revolution from the top. Other gods were first neglected, then attacked. After a few years at Amarna, Akhenaten sent teams of workers around the country, gouging out the image and the name of the god Amun in temples. Amun had been the state god of Thebes, in present-day Luxor, and Akhenatens decision to move his capital might have been a way to break the power of the established priesthood.

The king constantly tinkered with his appearance in statues and portraits. His features were often strangely exaggerated: massive jaw, drooping lips and elongated, otherworldly eyes. He was portrayed with his wife, Nefertiti, in unusually intimate and natural poses; one scene even features the king and queen about to get into bed together. In portraits they often kiss and caress their six daughters. Nefertiti was named co-regent and she appeared in scenes that had previously been restricted to male kings: inspecting prisoners, smiting bound captives.

The Egyptian faith was radically stripped down: fewer gods, fewer rituals. In the tombs that court officials commissioned for themselves on the cliff walls behind Amarna, there were no more references to Osiris or the traditional afterworld. Akhenaten had temples constructed without roofs, to make sun worship more direct. Rituals must have been brutally hot. The king of Assyria wrote an angry letter: Why should my messengers be made to stay constantly out in the sun and die in the sun?

But for Akhenaten, the desert represented a purer past. He tried to be as ancient as possible, Christian Bayer, a German scholar, told me. Of course he also wanted to do something totally new. He made a revolution out of something ancient.

By fashioning this revolution from the ancient, Akhenaten also intimated the future. He reminds us that the fundamentalist is never near the fundamentals he is always at a distance, gazing back at the unattainable. Kemp writes: Akhenaten appears to represent an early example of a widespread trend in the history of piety, towards greater austerity in conceptions of the divine. Its similar to the modern Islamists, whose revolutions in Iran, Afghanistan and Egypt always envisioned a return to some distant, purer past.

In creating his new rituals, Akhenaten pioneered political techniques that remain effective today. Some slogans of modern political revolutionaries Make America Great Again echo the way that Akhenaten and other pharaohs manipulated nostalgia in order to justify change. Amarna tombs show the king reviewing military parades in scenes that foreshadow the processions that became popular under Anwar Sadat. Another innovation was the palace-balcony scene, in which the ruler looks down on admiring subjects, like Hitler above the Heldenplatz. In Akhenatens new city, court officials erected garden shrines with pictures of the royal couple, the same way that Hosni Mubaraks portrait would someday hang in bureaucrats offices.

We have no idea what average Egyptians thought while all of this was going on. Akhenaten died suddenly, in the 17th year of his reign. The city was still being constructed; the kings tomb was unfinished. The heirloom that he chose to be buried with was a 1,000-year-old stone bowl inscribed with the name of the pharaoh who had built the Great Sphinx.

The revolution collapsed almost immediately. Two years after Akhenatens death, the throne was occupied by his only son, Tutankhamun, who was no more than 10 years old. Tutankhamuns mother was not Nefertiti, and he issued a decree criticising conditions under his father: The land was in distress; the gods had abandoned this land. Soon, the Egyptians vacated their city in the desert.

Less than a decade into Tutankhamuns reign, he also died unexpectedly. He had been married to his half-sister, and their only two children were both stillborn finally, inbreeding put an end to the familys reign. After another king ruled for a brief period, Horemheb, the head of the army, declared himself pharaoh possibly the first military coup in history.

Horemheb declared a wehem mesut a renaissance. It was another piece of prescient politics; more than two millennia later, when the Muslim Brotherhood came to power in the wake of a revolution, they called their program Al-Nahda, the Arabic word for renaissance. But Horemhebs renaissance was one of forgetting, not of remembrance. The king began to dismantle Amarnas temples and palaces, and his successors accelerated the destruction. They sent workmen to Amarna to destroy every statue of Akhenaten and Nefertiti they could find. The kings coffin was smashed; royal names were obliterated from inscriptions. The rulers of the dynasty that succeeded Horemheb, the 19th, referred to Akhenaten only obliquely, with phrases such as the criminal and the rebel. This campaign of damnatio memoriae was so successful that Akhenaten disappeared from history for 31 centuries.

By the time his name was rediscovered by foreign archaeologists, in the mid-19th century, the world had caught up with the ideas of the rebel king. During an age of revolutionary movements, everybody wanted to claim Akhenaten. As Montserrat notes in his book, Akhenaten appealed to groups that felt marginalised, and they applied the kings own strategy of seizing the past. If somebody wanted more acceptance for environmentalism, or gay rights, or Nazism, or racial equality or some other issue, he could turn to the image of the iconoclast king as proof that such ideas were rooted in antiquity. Often the evidence was flimsy; largely on the basis of a few images that seemed to show Akhenaten holding hands with a male successor, some early scholars speculated that he was gay or bisexual. (Nowadays, most Egyptologists believe that the other figure was in fact Nefertiti under another name.)

Part of the kings appeal was his survival: even the targeted campaigns of his successors failed to destroy his memory. In some cases, acts of destruction turned out to be a form of preservation. Ramesses the Great dismantled more Amarna temples and palaces than anybody else, and he used the stone blocks that are now known as talatat for his own temples. Many Amarna talatat were beautifully inscribed, and Ramesses had them placed deep in the foundations of his structures, as a way of burying the heretic kings work. But over the course of millennia, the temples of Ramesses the Great were themselves slowly dismantled, until only the foundations were left.

Its a cycle of recycling, Raymond Johnson, an Egyptologist who directed the University of Chicagos research centre in Luxor, told me. The ultimate irony is that what Ramesses thought he was hiding away is now exposed. How could you hide it better than putting it in the foundation of a temple? But we know more about Akhenatens temples than we do about Ramessess.

Johnson had trained as an artist, and he believed that Akhenaten must have been wildly creative, despite his despotic tendencies. This is another reason that the period has always drawn attention: many artefacts, such as the famous limestone bust of Nefertiti, are stunningly beautiful. Naturalistic scenes portray the changing emotions and appearances of the royal family; even Nefertiti is shown with wrinkles as she ages. This preoccupation with the present rather than the eternal is one of the hallmarks of Amarna art, writes Johnson. It is almost as if the two dimensions of Egyptian time the eternity of the gods and the endlessly repeating present of nature and humanity had converged.

While Akhenatens faith was quickly rejected after his death, the art seems to have been irrepressible. The Amarna style influenced subsequent periods, including the court art of Ramesses the Great. And I noticed that scholars who focused on artistic representation, such as Raymond Johnson, tended to have a softer view of Akhenaten than Barry Kemp, who dealt with the material traces of the city.

Marsha Hill, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, sometimes pieced together fragments of statues that had been destroyed during the anti-Akhenaten campaigns. She told me that handling the pieces made her feel positive about Akhenaten. Everybody likes revolutionaries at some level, she said. Someone who has a real good, strong idea that makes it seem like things are going to get better. I dont see him as destructive. Of course, it didnt work out. It usually doesnt. Steam builds up under the ground until it explodes, and then you have to put it all together again.

After we took a family road trip to Upper Egypt in the Honda, my daughters became obsessed with Egyptology. They roleplayed, because they liked the way the letters of the names lined up: Ariel was Akhenaten, Natasha was Nefertiti. Something about ancient Egypt naturally connects with children, who seem to understand it at a visceral level: the animal-headed gods, the beauty of the hieroglyphs. Virtually every foreign Egyptologist I met had started his or her career with a childhood obsession. Kemps father had been stationed with the British army in Egypt during the second world war, when he sent back pictures of relics that fascinated his son. As a girl in Oklahoma, Marsha Hill had loved a book about an Amarna princess. Raymond Johnson had been entranced by National Geographic articles about Egypt while growing up on a lonely chicken farm in Maine.

This experience seems less standard for Egyptians in the field. Zahi Hawass, who is the most prominent native Egyptologist, told me that originally he wanted to be a lawyer. He also studied to be a diplomat, but failed the oral exams. He entered the field of antiquities as essentially a last resort, but then he realised he loved the work.

For Egyptian Egyptologists, the starting point was often pragmatism. Mamdouh Eldamaty, an excellent scholar who became minister of antiquities in 2014, answered bluntly when I asked about his childhood interests. I always hated history, he said. He had hoped to become a doctor but failed to gain admission to medical school; after that, he studied commerce, only to realise that he hated business even more than he hated history. Like Hawass, Eldamaty had entered Egyptology as a third option, and then he discovered a gift for ancient languages.

The national relationship with the past is complicated. Average citizens take pride in pharaonic history, but theres also a disconnect, because the tradition of the Islamic past is stronger and more immediate. This is captured by the design of Egypts currency. Every denomination follows the same pattern: on one side of a bill, words are in Arabic and theres an image of some famous Egyptian mosque. The other side pairs English text with a pharaonic statue or monument. The implication is clear: the ancients belong to foreigners, and Islam belongs to us.

It surprised me that so many prominent sites were still being excavated by foreigners. Before Egypt, I had lived in China, where the authorities never allowed non-Chinese to play such a role in curating the nations past. But Egypt has a long legacy of colonialism, and one ironic outcome of the most recent revolution is that foreigners, and the funding they provide, have become even more crucial to Egyptology. In 2014, Eldamaty announced that tourism revenues from Egypts ancient monuments had dropped by more than 95% since 2010.

Eldamaty, like a number of other Egyptian scholars I talked to, was remarkably non-possessive about the field. When I mentioned the contrast with China, he rejected the idea that foreigners should be prevented from directing excavations. Whoever is qualified should do the work, he said. Foreigner or Egyptian, its the same.

Foreign scholars often made similar points, although I noticed a generational difference. Laurel Bestock, a young professor at Brown University, expressed discomfort with the situation, and even questioned the origins of her own love for the field. As a girl, Bestock dreamed of going to the Sahara after reading a series of mystery novels about Egyptology. I think this is part of our legacy of not confronting colonialism, she said. Our own interest was started so young. It wasnt a considered, adult interest; it was a childhood fascination. The academic interest grew out of the fascination. Its very hard for us to justify our own interest, because its essentially childish in its conception.

Perhaps it also reflects the elemental nature of ancient Egypt. So much of that lost world feels familiar, and so many of its ideas are foundational to the civilisation of the region, that it is hard to think about ownership. This is human heritage, Eldamaty told me. We cant talk about it as just Egyptian heritage. But Bestock had reconsidered the way she planned to work in Egypt, and believed that this is common among her younger peers. She said: Theres a difference between having a foreigner in charge of an entire site and having projects that are smaller and more collaborative from the beginning.

Adapted from The Buried: An Archaeology of the Egyptian Revolution by Peter Hessler, published by Profile Books on 2 May and available at guardianbookshop.com

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, and sign up to the long read weekly email here.

Recent Comments