They were West German teenagers on a school trip. He was a young man desperate to escape from East Germany. Thirty five years later, they tell their story

Its December 1984, a week before Christmas. Tina Kirschner and Barbara Kahlke, two 17-year-olds from West Germany, are sitting on a creaking red bus headed for the socialist part of their divided country. Theyre on a school trip, and the mood is boisterous: almost 40 teenagers singing along to Duran Duran. But once they cross the heavily guarded border, reality hits. The world theyre entering feels alien and forbidding. All around them, slogans celebrate the glorious achievements of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Yet as they pass through the crumbling town centres, the shops are empty. Here, only a couple of hours from their little hometown of Marburg, people have been queueing for basic groceries.

In a carefully staged encounter with local students, the girls are told that their impressions are wrong, that life here is good. When the East Germans insist that even their version of Coca-Cola is better than the wests, the planned rapprochement descends into a battle over soft drinks. Tina and Barbara are unsettled by the constant propaganda, the oppressive atmosphere. Its almost like visiting an open-air prison; after all, the people around them cant leave. Most of those who try to escape to the west are arrested and jailed. Some are shot, or blown up by mines in the death strip.

One day, the teenagers visit the medieval city of Erfurt for a sight-seeing tour. As some of them mill around the bus, a tall, gangly man in his 20s approaches, introducing himself as Bernd Bergmann. The girls are astonished to learn he was born in Marburg, before his mother took him to the GDR as a child. When he spotted their Marburg number plate, he wondered if they might know a friend of his.

The girls are hesitant at first, unsure what to make of him. But they are also curious, and Tina and a couple of others arrange to meet him in a cafe later in the day. Bernd tells them hes desperate to join his friend in Marburg. He has applied for an exit permit many times, but has always been rejected. Now hes considered a troublemaker. Hes lost his job, and is being harassed by the Stasi, the East German secret service. Tina is outraged: how can a government just lock its people up? The friends agree to meet Bernd again in the evening, in a noisy underground bar where they can talk more freely.

Later, the girls climb into the empty bus. Someone says, half joking: what if we take him across? For now, its just a thought experiment, almost a game. They look around the bus and notice a half-broken seat in the back row that can be tipped forward. One of them crawls into the space behind it. The others walk around the bus and check that she cant be seen through the back window.

Yes, they think this could work. At least, in theory.

***

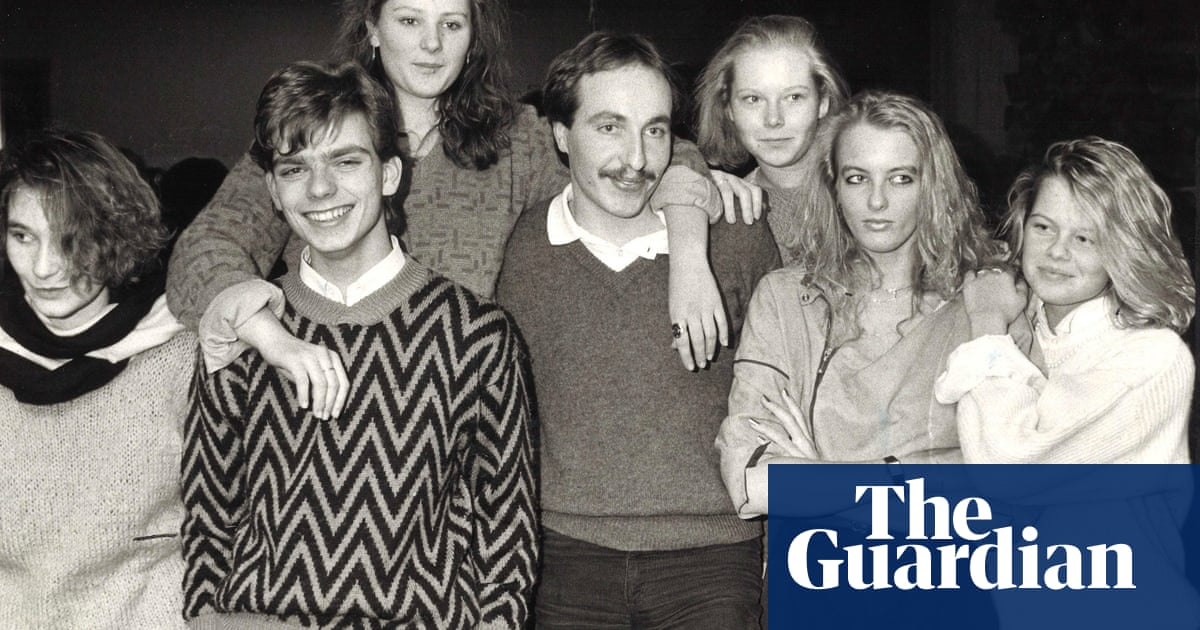

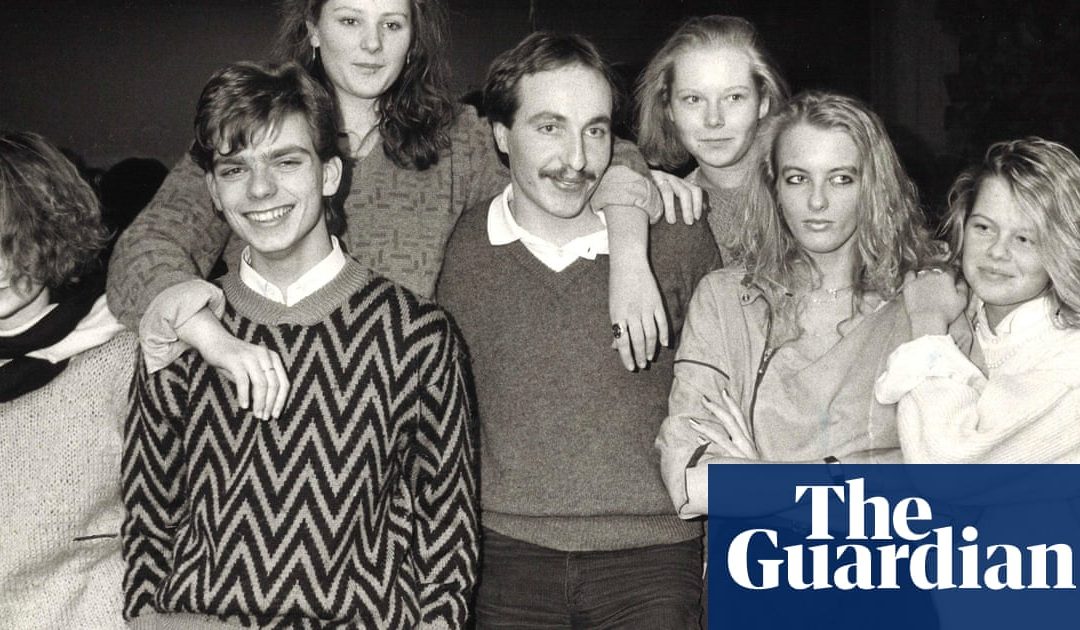

It sounds like a cross between a John le Carr thriller and the Famous Five: the schoolchildren who tried to breach the iron curtain. I stumbled across their story by chance, because I also grew up in Marburg, a quiet university town on the banks of the river Lahn. My brother went to the same school as Tina and Barbara. Through old letters and school reports, and Stasi records, I pieced together what happened how their giddy mission turned into a cold-war drama, triggered a small war at their school, and ended with their teacher being put on a secret service watch list. I tracked down that teacher, the schoolgirls, and the man ready to risk everything to get out.

It might seem odd, to arrange an outing to a dictatorship, but at the time of the school trip, east-west relations had been thawing a little. It reflected the contradictions of that era the desire for a rapprochement despite the intense rivalry, and the fact that many Germans had personal ties to the other side.

Barbaras father, for example, was a refugee from the eastern German provinces that are now part of Poland, arriving in West Germany at the end of the war. Her mother was from East Germany, but left before the border was sealed. They abhorred the division, but there was another factor that pricked Barbaras conscience. Like all German teenagers, shed learned about the countrys Nazi past at school, and the importance of moral courage. Indeed, the school trip to the GDR included a visit to a former Nazi concentration camp, Buchenwald. Barbara often wondered what she would have done back then: look away, or resist?

When I talk to her at her home near Hamburg, she tells me she had a clear sense that helping Bernd was the right thing to do. I think we just saw this amazing opportunity, she says. She describes the students determination: Were doing this, were going to pull this off.

Later that evening, the girls sneaked out of their youth hostel and into Bernds waiting Trabant. Barbara remembers being intrigued by the idea of the underground bar, and thinking that they might dance a bit. But in the car, the mood turned serious. Bernd signalled to them not to speak, in case the Trabant was bugged.

In the bar, they huddled in a corner. The girls told him about the hiding place. The more they talked, the more certain they were about the plan.

The next day, pretending simple curiosity, the girls asked their guides about border checks. They were told there were no heat sensors or dogs at the checkpoint they would be using, a rural crossing at Wartha-Herleshausen. Reassured, they sent Bernd a telegram from a post office: a Christmas greeting, a prearranged signal that the plan was on. As a precaution, they then burned their note with his address.

By now, their little group had grown to almost a dozen people; other classmates had got wind of the plan. That night, there was a heated discussion about the risks, and the girls decided to call it off. They would have to let Bernd down that morning, in person.

On their final morning, they visited the Wartburg, a medieval castle. Barbara went on the tour of the castle, keeping an eye on the teachers. Tina and the others stayed on the bus, feigning sickness, so they could inform Bernd of the change in plan. But then he was there, with all his stuff, and we had parked so conveniently, and it all seemed so easy. We decided at the last minute to pull it off, Tina tells me when I catch up with her on the phone.

The bus had stopped under an archway, sheltered from onlookers. Tina and the others asked the driver to open the back door for fresh air. One of them chatted to the driver, while the others let Bernd in through the back. The teenagers stood in the aisle to block the view. Bernd folded his almost 2m frame into the hidden space, and the girls piled their coats on top.

When the rest of the group returned from their tour, the helpers quickly occupied the back row. One girl happened to have some tranquillisers with her, and Barbara popped half a pill to stay calm. The bus pulled out of the parking lot. There was no turning back, Tina recalls. He was lying there in the back, and nobody knew anything just us.

As they approached the border, Tina and the others sang along to Tina Turner at the top of their voices to calm their nerves, Private Dancer and I Cant Stand The Rain. The bus stopped for lunch. Suddenly, there was a knock on the window: East German police. That completely floored me. We thought, Oh my God, were busted, Tina says.

But the policemen were interested only in the driver; hed parked badly and was told to move the bus. When they reached the checkpoint shortly afterwards, a uniformed guard got on to check their passports. He walked straight down the aisle, towards Barbara. I could really feel my heart beat, she says. I was really scared. Because he was standing right in front of us, only a metre from Bernd.

There was a knocking sound from outside: more guards, tapping the bus to check for concealed hiding spaces. Barbara tried to hide her fear. The guard paused, handed back their passports, turned around and left the bus.

The doors shut. They crossed the border.

Some 20 minutes later, one of their friends picked up the onboard mic and announced: Our guest today, live in our show: Bernd Bergmann from the GDR!

Barbara has a clear image of Bernd popping up from behind the back seat. Blood was trickling down the side of his chin. In his hiding place, shrinking from the guards as they knocked on the outside of the bus, he had bitten his lip.

Tina says she felt like a hero. We cheered, we were beside ourselves, we were super happy, which was totally stupid because thats how we She hesitates. Thats how that whole school war started.

***

School War was one newspaper headline in the weeks that followed. Marburg Schoolchildrens Tragedy was another. Decades later, it is impossible to entirely make sense of how the towns political faultlines were exposed. Some of the helpers on the trip have since died, as have two of the teachers. Those who are alive, and willing to talk, still seem scarred by the experience.

In his sunny, tranquil living room, Jrgen Beier pauses and tops up my coffee. The retired teacher still lives near the school where he taught for decades, in an idyllic suburb of Marburg. He has a vivid memory of the moment a stranger emerged from the back row of his school bus. He compares it to a car crash; all he could think about was what to do next. His students were celebrating, but he had to consider the practicalities: what should they do with Bernd now? What should they tell the parents, and the authorities? He knew this would have ramifications far beyond their little town.

You dont endanger your classmates and your teachers, he says, no matter how good your intentions. Beier had been one of the trips organisers. Hed thought their school, the Steinmhle, might even partner with an East German school, given the thawing political relationship. That obviously turned out to be rather naive, he says. With hindsight, you get the impression that we were under constant surveillance.

The school had to book the trip through a GDR-friendly travel agency, and a member of a communist organisation in Marburg had to accompany them throughout. I dont think he was a spy, Beier says of the minder. He was more or less a guarantee for the other side, that everything was a bit under control.

Others did spy on the group, though. After Germanys reunification, Beier found out through the newly opened Stasi archive that informants had kept an eye on the trip. Yet theyd somehow missed the bit where the teenagers hid an East German fugitive under their coats.

It was Beier who had to deal with the immediate aftermath of Bernds escape. After talking to the East German on the bus, he explained to his students what this meant for everyone. Legally, the situation was clear. Helping him had been a crime until they had crossed the border. In West Germany, it was no longer a crime: their government considered all Germans its citizens. The bus dropped Bernd off at a police station where he could formally enter the system, and in legal terms, he was free.

But the group had still put themselves in immense danger. In this tight surveillance state, 80% of escapees were arrested before they even reached the border. For the GDR, defections were a public humiliation. Failed escapees and their helpers were punished harshly. Only a couple of days before the trip, a West German mayor had been arrested by East German police for his minor role in an attempted escape years earlier; he was sentenced to six years in jail.

In the weeks after the trip, the West German government advised the teachers and students families not to travel to the GDR. For Beier, this meant not being able to drive through the transit corridor to see his best friend in West Berlin. Another teacher on the trip had a sister in the GDR, whom she could no longer visit.

We go through a stack of old school reports Beier has photocopied for me, all neatly labelled. One crucial document is missing. We go down to his study in the basement to find it. He rummages around, and pulls a brown cardboard folder from a shelf. Its a copy of a released secret service file his own.

It shows that, after the escape, the Stasi concluded that Beier had been the ringleader. Their report on the incident calls him a Fluchthelfer, someone who helps an escapee (it is in quotation marks as it was a West German term; East Germany called such helpers human traffickers). His relationship to the GDR is characterised as touristic, hostile. He is categorised as an operator of a subversive organisation. The file also says that an alert is to be issued should Beier ever re-enter the GDR. Attached to it is a Russian translation, since the order applied to all countries behind the iron curtain.

***

Shit! exclaims Barbara when I tell her about Beiers Stasi file. The poor man.

We are sitting in her family home in the small town of Bargteheide, near Hamburg, where she works as an artist. Around us are her sculptures and dreamlike landscape paintings. With Beiers permission, I show Barbara his file. She had no idea; it was released after she left Marburg.

Thats a nightmare for a teacher, definitely, she says of the escape. But she still feels that the school reacted too harshly. The students were questioned in front of the entire staff, and later given a warning with the threat of expulsion. One by one, they were asked to name the masterminds of the plan. Barbara said nothing: What was I supposed to do, make a cross against my own name? The group stuck together. They wrote an apology to their teachers and peers, explaining that theyd helped Bernd out of humanity. Parents weighed in, defending their children. Newspapers called the teachers heartless, and strangers sent furious letters. Politicians publicly supported the students; far-left papers attacked them. What had been a personal decision became a weapon in the east-west standoff.

For the school, there was one particular source of awkwardness. There were at least three teachers who had very friendly feelings towards the GDR, Beier says. He insists that these teachers did not influence the schools position. But Barbara and Tina both recall a distinct animosity from GDR-sympathising teachers. All their lives they had been told to be brave in the face of injustice. Now they were being treated like criminals.

After weeks of conflict, the threat of expulsion was softened to 16 hours of community service. The tensions hit Tina hard: I was quite emotionally sensitive back then, and all of that really distracted and upset me. At some point I just couldnt take it any more. She dropped out of school, two years before she would have graduated.

Barbara persevered. The next academic year brought different teachers. She started to feel better, graduated, left Marburg to study medicine and then took up painting. Today, she still wonders if they could have freed Bernd without putting others at risk.

We pause our interview for a lunch of soup and apple strudel. Barbaras youngest daughter, 12-year-old Luci, joins us. I ask her what she makes of her mums decision. I think its good that she did it, she says, confidently. I think I would have done the same. Barbara looks surprised, proud, and slightly unsettled.

What about the risks, I ask Luci. She pauses. I think I would have taken that risk. Because if it had been me in his position, and they had said no, I would have been very sad.

Tina has also told her children about the escape. She lives in Bali, where she works as an interior designer. Despite the personal cost, she has no regrets: Im just proud that we got him across, that it was a success, that we helped him. Because he just didnt want to be over there.

***

But what of Bergmann? The escapee from the GDR thrived in his new home. He now runs a successful insurance business in Marburg, and regularly drives along his old escape route to see clients in the former East Germany. For those he left behind, it was a different story.

I call Bernd several times while researching this article. Often, his wife, Birgit, picks up the phone. Birgit was Bernds girlfriend back in Erfurt, and according to German press reports, he kept her in the dark about the escape. Yet she apparently forgave him, later joining him in the west. A couple of times I ask after her side of events, but she gently deflects my questions.

Then, months after our first contact, I call her to verify some facts. When we get to the part where Bernd reportedly kept his plans from her, she hesitates. I knew about the escape, she says eventually. She carefully weighs her words, and adds: I guess you can write about that these days its harmless now.

What she tells me next takes me completely by surprise. At the time of Bernds escape, Birgit was 23 years old. She loved her job as a teacher, her friends and family. She felt that by focusing on those things, it was possible to carve out a good life in the east, to be happy there. But Bernd was different. He did not want to live in a dictatorship; he wanted to live in a democracy. Birgit recalls how much he yearned to live in the west, how determined he was to get there.

Immediately after he met the girls from Marburg, he told her about the plan. Her first reaction was to try to stop him. Of course I wanted him to stay, that was obvious. Because I didnt know when wed see each other again. It could have been a farewell for ever, she says. In the end they made a pact: if he reached the west, he would find a way to get her out, too. And if he was caught, she would support him, and visit him in prison.

It was Birgit, however, who almost landed in jail. After Bernds escape, the Stasi interrogated her and her family. She was told that if she refused to talk, her parents would lose their jobs. Again and again she was questioned. She was sacked from her job as a teacher. Despite the intense pressure, she managed to persuade the Stasi that she knew nothing. She endured months of surveillance, interrogations and threats. She and Bernd were able to write to each other, and speak on the phone, but all their exchanges were monitored. In 1986, she was finally granted an exit permit, and joined him in Marburg.

We were so much in love, and that gave us strength, she says. He is the love of my life. And vice versa. I mean, were still together! Its lasted.

By now I have heard from all the protagonists except Bernd. At first he tells me he will only be interviewed in person. We arrange to meet in Marburg, but then he cancels. He suggests doing the interview together with Barbara in Hamburg, but again changes his mind. We talk informally several times, and I hear his story in scraps down a patchy mobile phone line. He was so desperate to leave, he says at one point, that his alternative plan was to steal a helicopter from a Russian air base. He is full of praise and admiration for Tina and Barbara. But he also recalls how crushed he and his wife were when they later consulted their Stasi records, and read about the extent of their surveillance. It still puzzles me how the secret service missed his contact with the Marburg group. Perhaps the whole mission came together too quickly for them to intervene: within three days, he was out. And who would suspect a bunch of teens in a shabby red bus?

During our final phone call, I ask Bernd why he was so desperate to live in the west. Ich wollte Freiheit, he says: I wanted freedom. A few weeks later, he unexpectedly agrees to a reunion with Barbara. They meet at the place where it all began, the Steinmhle school in Marburg, having not seen each other in about three decades. I call Barbara afterwards to hear how it went. In her calm, thoughtful way, she says it was lovely to see Bernd again, and to talk about the escape. Throughout our interviews, she has been very modest about her role in it, reluctant to be in the spotlight. But towards the end of the call, she says quietly: That was a pretty great operation.

Sophie Hardachs novel, Confession With Blue Horses, about a girl growing up in East Berlin, will be published on 13 June by Head of Zeus. She will be talking about this story on the Guardians Today in Focus podcast on Monday 13 May.

If you would like a comment on this piece to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazines letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/11/schoolgirls-defied-the-stasi-across-the-border

Recent Comments