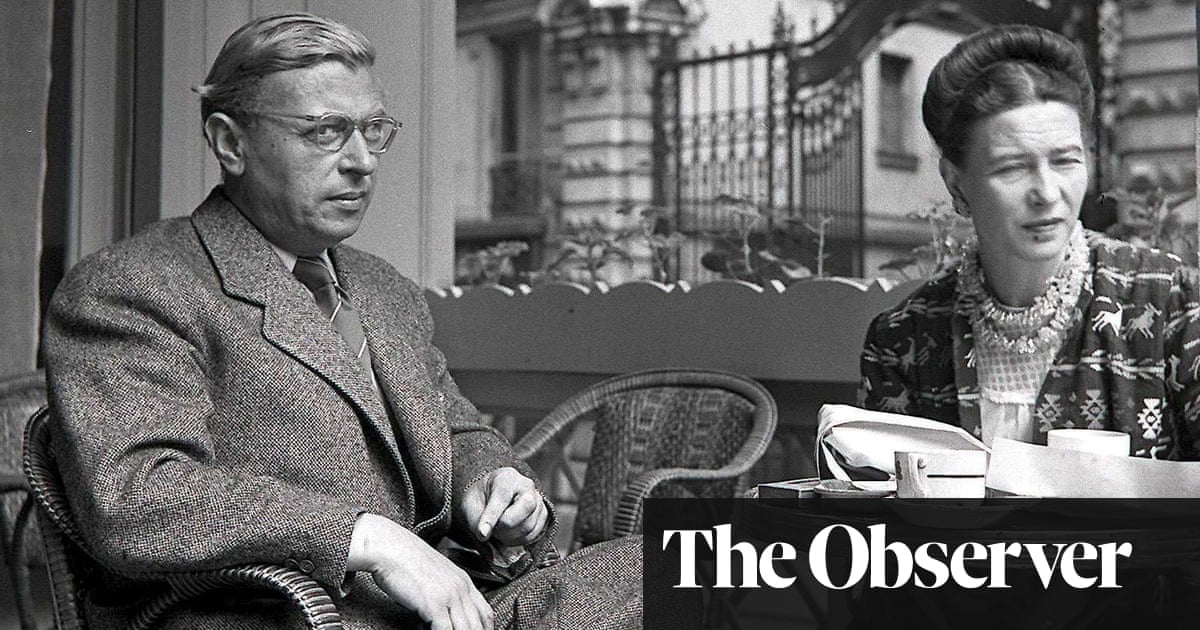

Journal founded by Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre closes after 74 years

Simone de Beauvoir called its Sunday afternoon editorial meetings the highest form of friendship, but after 74 years Les Temps Modernes, the monthly journal she founded with Jean-Paul Sartre, has closed.

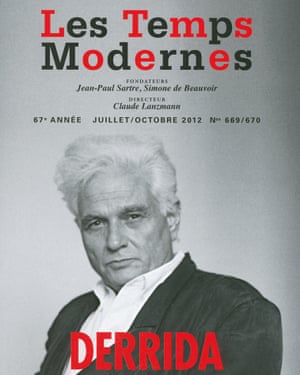

The death of its last editor, Claude Lanzmann, last July made the decision by its French publisher, Gallimard, to shut the magazine almost inevitable. Lanzmann, an early contributor and student of Sartre, had taken up the baton from De Beauvoir, a former lover, when she died in 1986. His passing broke the magic circle of history. Besides, who could today measure up to those three intellectual heavyweights?

Reading issues from its first decade feels as novel today as it did then. Its tone is original, the reportage reads like literature, the style is uncompromising, and the analysis combative. New Journalism is often considered to have emerged in New York in the late 1950s. But it could be argued it came from Paris in the late 1940s with Les Temps Modernes, which was among the first to break down the divide between literature and journalism.

The first issue in October 1945 provoked a big bang in journalism and politics, and not just in France.

Its manifesto was translated and published widely, including in Cyril Connollys Horizon in London. It read: Every writer of bourgeois origin has known the temptation of irresponsibility. I personally hold Flaubert personally responsible for the repression that followed the Commune because he did not write a line to try to stop it. It was not his business, people will perhaps say. Was the Calas trial Voltaires business? Was Dreyfuss condemnation Zolas business? We at Les Temps Modernes do not want to miss a beat on the times we live in. Our intention is to influence the society we live in. Les Temps Modernes will take sides.

To carry its distinctive voice far and wide, Les Temps Modernes (named after Charlie Chaplins Modern Times) could rely on a diversity of talented writers and philosophers from across the political spectrum. Communists, Catholics, Gaullists and socialists: philosopher Raymond Aron, Marxist phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, anthropologist and art critic Michel Leiris, and even Picasso, who had agreed to design the cover and logo.

The British writer Philip Toynbee contributed a Letter from London, while novels and essays the committee particularly liked were serialised prior to their publication or with a view to attracting a potential publisher. Les Temps Modernes was particularly interested in women, foreign writers, dissidents and original voices of talent.

Its first issue opened with an exclusive extract of the black American writer Richard Wrights Fire And Cloud, whose description of lynch mobs in the deep American South shocked French readers and shed light on racial discrimination in America in lyrical and violent language, superbly translated by Marcel Duhamel.

In the following issues, Samuel Beckett, Violette Leduc, Nathalie Sarraute, Boris Vian, Jean Genet and many others found a home at Les Temps Modernes. Troubles in Indochina and north Africa were first reported in Les Temps Modernes and the journal embraced the anti-colonialist cause with passion and courage.

A laboratory of new ideas and a talent agency rolled into one, Les Temps Modernes was also existentialisms incubator. Sartre concluded the first issue with an article entitled The End of the War, in which he wrote: Peace is a new beginning but we are living an agony War has left everyone naked, without illusions; they now can only rely on themselves and this is perhaps the only good thing that has come out of it.

This pessimism stung many readers, but it also felt like a new honesty, one which called for immediate action. There was something fresh, stimulating, liberating in it. Responsibility for our actions as much as for our inactions, for our commitment or lack of it, was ours and ours alone. No more excuses. Gallimard had agreed to finance the journal and to give the team a small office in the heart of Saint-Germain-des-Prs, at 5 rue Sbastien Bottin.

Extraordinarily, Sartre committed himself to receiving anyone who asked to see him at the magazines office every Tuesday and Friday afternoon between 5.30 and 7.30. This promise was even printed at the front of the magazine, along with the telephone number Littr 2891, where he could be reached. This was democracy and public debate in action.

This led to heated debates and some tragicomic scenes. In her memoirs, De Beauvoir recalled Abbot Gengenbach, a half-defrocked priest, who became a regular visitor. A surrealist, he drank heavily, cursed the Church and went out with women. He then locked himself up for a few weeks in a monastery to make amends.

On another Tuesday afternoon the receptionist rushed to De Beauvoir: a reader whose text had been turned down by the editorial committee had just cut open his wrists.

After Les Temps Modernes made its position on abortion clear, advocating its legalisation, people started queuing in front of its office to ask the secretary, Madame Sorbet, for the details of doctors who would discreetly perform this illegal medical act, which at the time was punishable by life imprisonment, and in some cases even death. Modern and dangerous times.

Les Temps Modernes inexorably followed the political peregrinations of Sartre and De Beauvoir. As the cold war froze public discourse into bloc politics for decades, it too sometimes lost itself in leftist obfuscation. It then lacked the clarity of its glorious beginnings, but it is the impact made in those first years that will be its lasting legacy.

Recent Comments