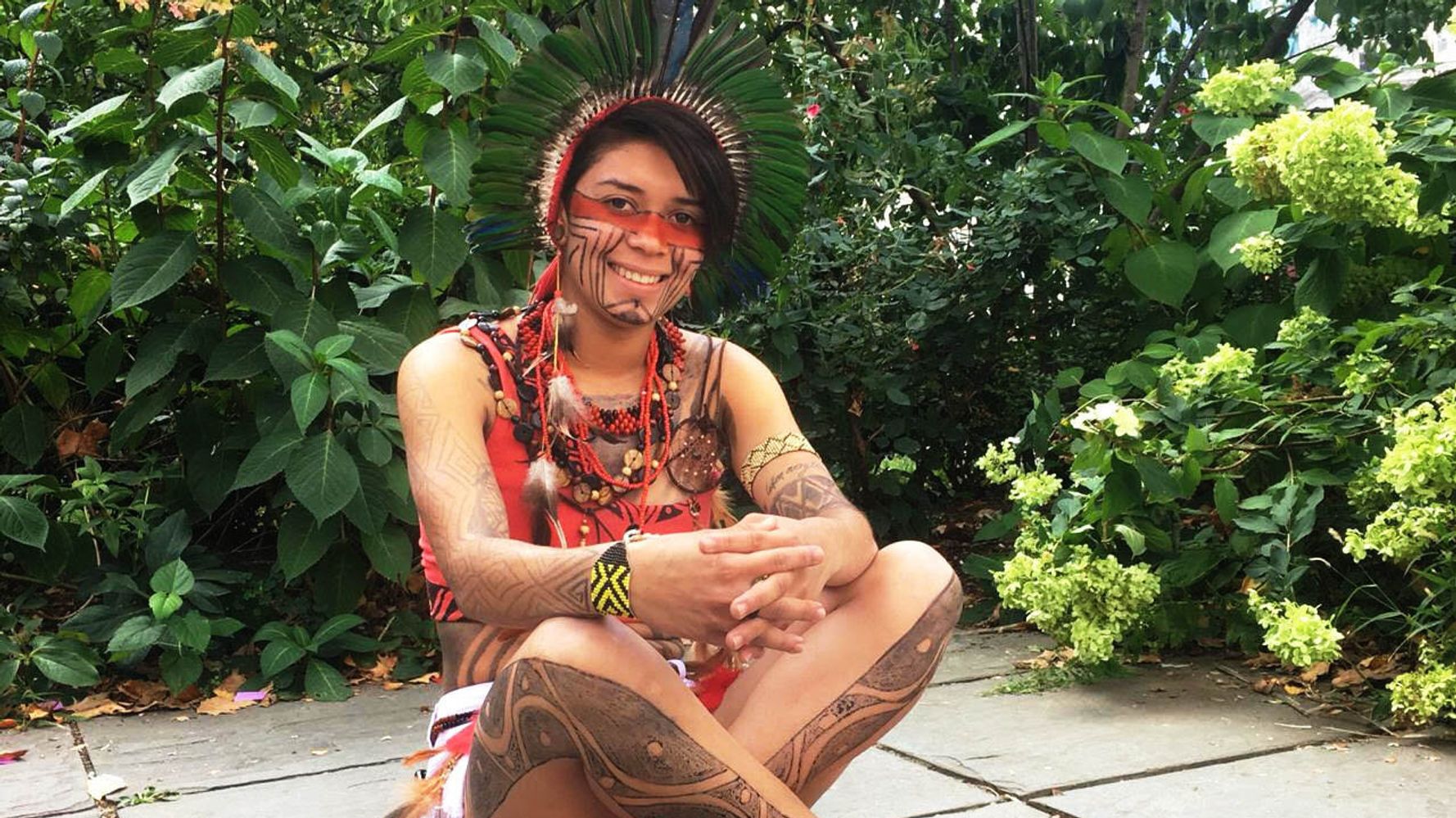

NEW YORK ― Last month, as a record outbreak of fires in the Amazon threatened to push the vulnerable rainforest closer to destruction, 19-year-old Artemisa Xakriabá begged the world to realize what the rapid obliteration of Brazil’s environment means for indigenous people like her.

“We are fighting for our lives,” Artemisa said in a speech during the youth climate strike in Manhattan, not far from where Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, would later tell the United Nations that climate change is a “globalist” conspiracy, deny that the fires were devastating the Amazon, and place blame for the blazes on indigenous people.

No one may better exemplify the urgency of the planet’s crisis than Artemisa, a member of two communities that have produced the fiercest leaders in the fight against climate change and environmental destruction: She is a teenager in a world where millions of young people have begged their elders to forcefully and immediately address climate change. And she is a member of Brazil’s Xakriabá tribe, part of a community that faces the most immediate and disastrous effects of the world’s war on the environment, which has left tribes in Brazil and elsewhere fighting not just against climate change but for their very existence.

“We are fighting for our sacred territory,” Artemisa said. “But we are being persecuted, threatened, murdered, only for protecting our own territories. We cannot accept one more drop of indigenous blood spilled.”

Artemisa came to New York, she said, to “shout for help in the name of all Brazilian youth,” and to call for protections for the indigenous peoples around the world whose battle to save the planet is driven by a “direct connection to the earth and the forests.”

“We often say that nature is our mother, because she gives us life, she gives us food,” Artemisa said. “We have a duty to defend her.”

Bolsonaro’s Indigenous ‘Genocide’

Indigenous peoples live on roughly 25% of the planet’s land, and their territories are home to 80% of the planet’s diverse array of plant and animal life. The World Bank has said that indigenous peoples have an “enormous” role to play in protecting vulnerable environmental areas that are vital to limiting the effects of climate change. In August, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change argued for the first time that protecting indigenous lands is an essential element in the fight to save the planet.

Artemisa was just 7 years old when she and other students from the Xakriabá tribe helped reforest 15 riverside areas near their traditional lands in the southeastern state of Minas Gerais. In Brazil, 300 indigenous tribes live on 13% of the country’s lands, and have helped protect more than 400 million square miles of the Amazon rainforest from deforestation.

But that also means that no one is more at risk from the effects of climate change and environmental destruction than tribal peoples, and in Brazil, they have become even more vulnerable in recent years, as conservative governments rolled back environmental and tribal protections, and rates of deforestation began to rise again.

Bolsonaro poses an even bigger threat. In his nearly three decades in Brazil’s congress, the former Army officer regularly disparaged indigenous people. In 1998, Bolsonaro called it “a shame” that Brazil’s military had not been as “efficient” as the armed forces in the United States, who had managed to “exterminate the Indians.” In 2015, he said that indigenous Brazilians should not have protected territories in the country because “they do not speak our language, they have no money, [and] they have no culture.”

During his 2018 campaign for president, Bolsonaro pledged to gut environmental agencies and end the practice of officially designating indigenous lands for protection so that farming, mining and other interests could operate more freely in the forest and on protected lands. Tribal leaders warned that his approach to their lands risked triggering a “genocide” of indigenous peoples.

Even before Bolsonaro took office in January, the combination of the previous government’s paring down of environmental regulations and the right-winger’s promise to go even farther gave license to farmers and miners to target indigenous lands. And they did: In 2018, 135 indigenous people were killed, a 23% increase from 2017, according to Brazil’s Indigenous Missionary Council.

This year, Bolsonaro has attempted to gut the government agency in charge of protecting indigenous lands and people, and his allies in Brazil’s congress are preparing legislation to allow mining and agriculture on those lands. Across the first nine months of this year, there were 160 reports of land invasions or illegal logging and mining on indigenous lands across Brazil, the Indigenous Missionary Council said, citing preliminary data. That was double the number from the same period in 2018.

We often say that nature is our mother, because she gives us life, she gives us food. We have a duty to defend her. Artemisa Xakriabá

In July, miners invaded an indigenous reserve and killed a prominent tribal leader. In response, members of the Wajapi community asked the government for protection from land invaders who had been dressed in military fatigues and wielded rifles. In response, Bolsonaro initially questioned their claim that a killing had occurred. “The president is responsible for this death,” an opposition senator told The New York Times.

Brazil is home to more uncontacted tribes than any other country, and has made efforts in the past to protect them. But in October, Bolsonaro’s government suddenly fired its leading expert on uncontacted peoples, prompting experts to warn that they too were at risk of genocide.

“All the claims that indigenous peoples of Brazil have been making [about Bolsonaro] are true,” Dinaman Tuxa, the executive coordinator of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil said after Bolsonaro’s speech to the U.N.

And as in the United States — where tribes led the protests that erupted against a pipeline project in the Standing Rock Indian Reservation and pushed back against President Donald Trump’s efforts to open the Bears Ears National Monument to mining — Brazil’s indigenous tribes and the organizations that represent them have hardened their efforts to fight back, and sought help and attention from tribal leaders waging similar battles around the world.

‘We Are Not Alone’

While Bolsonaro and Trump have formed a forceful anti-climate alliance, indigenous leaders across both countries have joined forces, too. In March, U.S. Rep. Deborah Haaland (D-N.M.) ― who in 2018 became one of the first indigenous women ever elected to Congress ― joined Joenia Wapichana, the first indigenous woman elected to Brazil’s legislature, to write an op-ed slamming Trump and Bolsonaro for “taking extreme action to strip the hard-earned rights of indigenous peoples to the benefit of extractive industries and commercial farming.”

As the fires raged in the Amazon earlier this year, indigenous activism intensified. Artemisa was among the thousands of protesters who participated in the first-ever Indigenous Women’s March in Brasilia, the capital, to protest Bolsonaro’s destructive environmental policies and his attempt to gut protections for indigenous peoples and their lands. It was an unprecedented show of force from tribal women from Brazil, Bolivia — which has also experienced devastating outbreaks of fires this year — and other parts of the continent. Brazilian indigenous leaders have continued protesting across the world since.

After that march, a coalition of tribal youth organizations from across South America and East Asia, where indigenous tribes are also facing threats due to the destruction of forested areas, chose Artemisa to serve as their representative at September’s youth climate strike events in Washington and New York. In D.C., she met with members of Congress about the Amazon fires and the urgency of climate change, and participated in a youth climate strike during which students from around the world marched on the Capitol.

In New York, she joined a host of tribal leaders who had come to counter not just Bolsonaro but also the corporations and business interests that have helped put the Amazon (and the planet) at risk: Across the city, indigenous leaders participated in protests against financial institutions and other companies that they say have continued to exacerbate climate and environmental crises.

After Bolsonaro and Trump spoke at the U.N., where both shrugged off concerns about climate and peddled conspiracy theories, the Brazilian indigenous activists organized an event to respond to them within hours.

“Even with our lands being burned and our blood dripping on our land, we bring here the screams of the people,” said Sonia Guajajara, the director of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil. “On top of fear, there is courage.”

“If there is any hope today, it is that we are not alone,” she continued. “The experience of other indigenous leaders and people around the world [is working] together to become stronger in defense of the indigenous people of Brazil.”

‘Our Future Is Connected’

If anyone has shared tribes’ sense of urgency about climate change, it is young people, millions of whom have protested across the world to demand that older politicians take immediate action to protect the planet and their futures.

“I am also here as a young woman, because there’s no difference between an indigenous young female activist like myself and a young female activist like Greta,” Artemisa said in her climate strike speech, referencing Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teenager who sparked the global youth climate movement when she walked out of school to protest inaction from world leaders on the issue. “Our future is connected by the same threads of the climate crisis.”

Bolsonaro’s conspiratorial response to the Amazon fires has risked making Brazil a pariah on the world stage, as countries like Norway and Germany have pulled investments into the country to protest his climate denial, and France and the European Union have threatened harsher actions.

Inside Brazil, some of the country’s youngest political leaders have joined activists like Artemisa in pushing back against Bolsonaro on climate.

Tabata Amaral, a 25-year-old congresswoman from São Paulo, opened a recent event in the United States by apologizing for Bolsonaro’s refusal to tackle climate change, and promised that younger Brazilians were aligned with their counterparts elsewhere in demanding immediate action on the issue.

“This is our future, and even though maybe Bolsonaro and most of the Congress can get away and never live to see what’s going to happen with the world, in 10, 20 or 30 years the world will be completely different if we don’t do anything,” Amaral told HuffPost. “It’s not an option for me, it’s not an option for us. It’s a matter of our future. We are the ones who are going to have to live through this, we don’t have the time to wait. We have to act now.”

The number of fires in the Amazon fell in September. But the destruction hasn’t stopped: Brazil has lost nearly 3,000 square miles of forest so far this year, and the Amazon is fast approaching a “tipping point” past which it won’t recover, scientists warn. And threats to tribal lands in Brazil, the U.S., Indonesia and Africa have only intensified, even as international attention to the fires has waned.

“I don’t know if we’ve made the world pay enough attention to our cause, but I believe this is our biggest mission here. So we will continue to fight,” Artemisa said. “Regardless of what the president decides, whether he will support us or not, we have to go on.”

Recent Comments