Not everything is perfect as reflected in political flux but the region is wealthier and healthier than ever before

Maciej Grabski looks out over a panoramic view of the Baltic Sea, from the 32nd floor of the Olivia Star tower in Gdask, Poland.

My children never saw the dark, devastated atmosphere that I remember from the 1980s, he says. Many people take things for granted now.

The tower, built by Grabskis construction company, is the centrepiece of a new business development on the outskirts of Gdask, and filled with the offices of multinational companies. It is next door to the squat, concrete Olivia sports hall, where the Solidarity trade union movement held its first congress in 1981, heralding the beginning of the end for communism in the region.

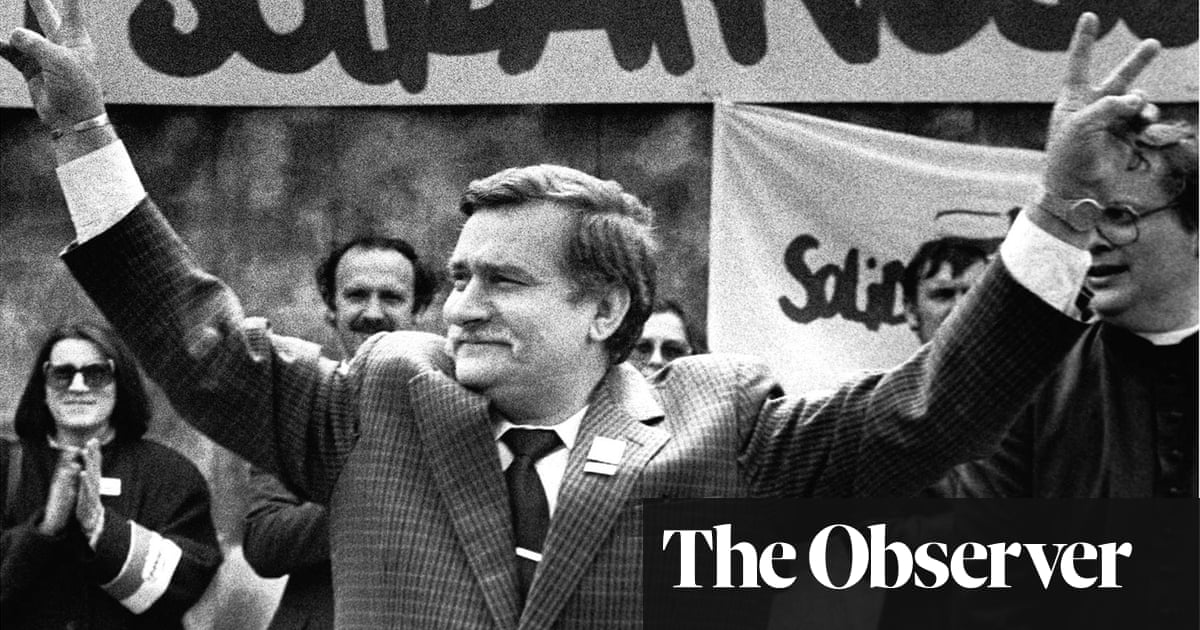

The economic demands of Solidarity, which had sprung up at the huge Gdask shipyard and was led by Lech Wasa, rippled through Poland and then the rest of central and eastern Europe during the 1980s. By the end of the decade, borders were open, regimes collapsed and the Berlin Wall, concrete symbol of 45 years of European division, was being pulled down.

What happened next was extraordinary, painful and unpredictable, as an entire region lurched into uncharted territory. Progress was fitful, messy and often unevenly distributed, sowing the seeds in some countries for the recent rise of populism.

But 30 years on from the heady days of autumn 1989, a range of metrics demonstrate that the transition from communism to capitalism has been a remarkable success.

Central and eastern Europe over the past 30 years has witnessed one of the most dramatic economic spurts of growth that any region of the world has ever experienced. People live longer, healthier lives. Air quality is better, and individuals are on average twice as wealthy.

This is the golden age for the region, says Marcin Piatkowski, a Polish economist who recently authored a book called Europes Growth Champion, about the meteoric rise of Polands economy over the past three decades. The whole region has been successful, as reflected in the fact that on average, no Bulgarian, or Romanian or Pole has ever lived better than they do now, both in absolute terms and in relative terms compared to the west.

Such optimism often feels misplaced, given that many people in the region still feel left behind. But the statistics show that since 1990, the Polish and Slovak economies have grown more than sevenfold, and those of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and the Czech Republic more than fivefold.

At the same time, the nations remain some of the most equal in the world, as measured by the Gini coefficient (one of the leading measures of wealth distribution).

There have been benefits when it comes to quality of life, too. In 1990, the average Hungarian, Latvian or Romanian did not live to see their 70th birthday, and life expectancy in other east European countries was not much better. Since then, longevity has surged as much as 10% in some parts of the region, and east Europeans are now more likely to be nearer 80 than 70 when they die.

Grabski, born in Gdask in 1968, has a story similar to many of the generation of Polish entrepreneurs in the years after the collapse of communism. Young and enthusiastic as the transition came, he eagerly sought out any economic opportunities going. His first business involved repeated trips to Hamburg, where he would sleep in the car and return with a carload of spare automobile parts, which he could sell on for a profit. Later, he invested money in an internet startup, and then into construction. He now runs one of the citys biggest companies.

The shock therapy reforms that speedily pushed Poland and other countries in the region into capitalism have come in for criticism, but Leszek Balcerowicz, the architect of Polands reforms, still believes they were the best option for the country in the circumstances. If you move fast from a bad system to a better one, you release new forces for growth, he says in an interview at the Warsaw School of Economics, where he is now a professor.

While communism left the region an economic basket case, it did also provide some of the seeds for growth: well-educated societies with low levels of inequality. And crucially, unlike in Russia and Ukraine, central European countries largely avoided a situation where a few people walked off with the majority of the prized former state assets.

Particularly in Poland, the transition led to a class of entrepreneurs like Grabski, rather than a small group of oligarchs. We had the Solidarity movement in the factories and they were like a watchdog. So directors couldnt go into shabby deals like in Russia, says Balcerowicz.

Life under capitalism

Fifteen years after the transition, Poland and seven other former communist east European countries joined the EU. With much of eastern Europe becoming part of the single market, it could be integrated into western European supply chains. For smaller businesses, it also meant operating in an improved institutional setting and convergence with EU standards. Joining the EU was the key moment, not because of subsidies, but because of frameworks: anti-monopoly rules, environmental protection and so on, says Grabski.

In some countries in the region, these institutional frameworks are still under attack from governments, but the situation compared with neighbouring Ukraine, for example, where the courts, police and tax authorities are hopelessly dependent on political and big business interests, is incomparable.

Life under capitalism was not rosy for everyone. At the vast Gdask shipyard, where Solidarity was born, the majority of orders came from the communist bloc and dried up after the transition.

The shipyard was kept afloat with government subsidies, but these were deemed unfair according to EU competition laws. The shipyard was divided into several private enterprises, and little actual shipbuilding is still taking place. Many other communist-era factories across the region have gone the same way, unable to adapt to market conditions.

But in place of the hulking shipyard, a number of smaller companies building yachts have sprung up in Gdask and elsewhere on Polands Baltic coast, and many of them have become successful.

However, if there is one factory that symbolises both central Europes growth over the last three decades and the potential pitfalls going forward, it is not the Gdask shipyard but the Audi plant at Gyr, in north-west Hungary.

Audi first invested in the site in the early 1990s when it was a moribund heavy machinery factory for mainly communist bloc clients.

Things took off when Hungary joined the EU in 2004 and could be integrated fully into the manufacturers supply chain. Today, Audi Hungaria is a modern-day capitalist version of a Soviet monogorod, or one-factory town. The vast complex on the outskirts of Gyr is a set of nondescript white hangars linked by an internal road system, and the plant has its own restaurants, medical clinic, fire station and postal service.

Every single Audi TT in the world is assembled here, while engines for many other models are also produced and shipped to Germany and elsewhere for assembly. In one vast hall, giant yellow Japanese robots whoosh and whir their way through the process of assembling the car bodies, cutting, welding, applying adhesives and piecing the cars together with minimal human input. Workers scurry between the halls, many with colour-coded polo-shirt collars denoting their status on the assembly line.

The plant has over 13,000 employees, and when subcontractors and affiliated businesses are taken into account, it is estimated that between 25,000 and 30,000 people in Gyr work in the automobile industry, which could amount to as much as half of the working-age population.

While Poland is more diversified, by virtue of being the regions biggest economy, for smaller countries in the region, the dependence on the German car market is huge, and some worry about the effects of a slump in the market on places like Gyr. If Volkswagen cant sell to China, Slovakia gets hammered the next day, says Piatkowski.

Going forward, the key will be moving away from an economic model of western European countries outsourcing production to the east, and towards one that sees ideas and innovation developed inside the region. Only in this way, analysts say, will the countries of the region be able to fully close the gap in wealth and living standards with the other half of Europe. So far, however, there is little sign of the spending on research and development, or institutional reforms, that would be required for such a long-term shift.

Smart people across the region understand that the growth model is over, but whether real change is politically feasible is another question, says Milan Ni, head of the central and eastern Europe programme at the German Council on Foreign Relations. What I see is that businesses are looking for loopholes rather than changing the overall policies.

This kind of supply-chain relationship amplifies regional disgruntlement at being regarded a second-tier backwater by old Europe. Thirty years since the Velvet Revolution, some of those who helped bring down communism in 1989 are now supporters of populist governments who accrue political capital by attacking the EU.

Lszl Nagy, one of the organisers of the pan-European picnic in 1989, which presaged the fall of the Berlin Wall by allowing hundreds of East Germans to cross the Iron Curtain from Hungary to Austria and onwards to West Germany, complains that western Europe treats the new states like the doormat of Europe, with a condescending and patronising attitude.

Additionally, while the statistics may show that on average even the poorest parts of society are better off than they were 30 years ago, this is little comfort to those in former industrial areas or rural regions where there is an overwhelming sense of decay; indeed, that decay can feel ever more pressing when compared to the progress experienced in shinier areas.

Quick guide

What is the Upside?

Ever wondered why you feel so gloomy about the world – even at a time when humanity has never been this healthy and prosperous? Could it be because news is almost always grim, focusing on confrontation, disaster, antagonism and blame?

This series is an antidote, an attempt to show that there is plenty of hope, as our journalists scour the planet looking for pioneers, trailblazers, best practice, unsung heroes, ideas that work, ideas that might and innovations whose time might have come.

Readers can recommend other projects, people and progress that we should report on by contacting us at theupside@theguardian.com

Not everyone is convinced that the impressive statistics tell the whole story. Jolanta Banach, a former Polish finance minister from a leftist party, puts much of the popularity of the countrys current populist government in smaller towns and villages down to the unequal access to public services and infrastructure: while big cities in Poland are now linked by modern fast trains, public transport in rural areas is often poor, an issue across the wider region too.

Public health and education services are generally in better shape than 30 years ago, but also remain underfunded. When you look at the Gini factor, its not so bad, but that hides a lot of things. What you dont see in the statistics is the uneven access to public services and infrastructure, says Banach.

The introduction of freedom of movement with EU accession has also led to millions of central and eastern Europeans heading west over the past 15 years. On the one hand, this has provided opportunities and experiences that were unimaginable to the previous generation who were stuck behind the Iron Curtain, but it has also combined with declining birth rates and a fear of immigration to contribute to shrinking societies.

In the three decades since independence, the populations of all the regions countries have shrunk. Latvia has lost more than a quarter of its population, Bulgaria and Romania around a fifth. With higher salaries a short and easy flight away, the process was inevitable. In parts of the region, this has led to chronic shortages of doctors and other skilled workers.

In the long run, if the countries of central and eastern Europe can continue to catch up with the west, many of the emigres will be drawn back. With Brexit stalking the UK, there are already anecdotal signs of an incipient return. There are flights from London and other western European hubs to dozens of cities in the region, often cheaply.

We havent lost these people, says Piatkowski. The form of emigration has changed. In the 19th century a redneck from the Polish mountains would move to America and youd never hear of him for 100 years. Now you can get a 20 Ryanair flight back to Krakw.

As the economic gap between the east and the west of the continent continues to narrow, it is possible that many of these people will eventually return to their home countries, bringing with them money, skills and networks developed during their time abroad.

For all the problems, Piatkowski says its worth acknowledging just how fast things have improved. Poland has moved from 25% of German income levels 30 years ago to 60% today. You cant expect Poles to completely catch up with Germans within one generation. Its only natural for people to aspire to a good life as quickly as possible. But its just unrealistic for this to happen. The whole region has been the dark periphery of Europe for the last 1,000 years, he says.

Wasa, Solidaritys leader and post-communist Polands first president, who was in charge when the shock therapy reforms were made, has become a marginal figure on the Polish political scene, and his cantankerous criticisms of the current government are sometimes seen as counterproductive even by the opposition. But he is still respected for his role in bringing the country out of communism.

Reflecting on todays economy, he thinks neoliberal economies require regulation to make sure they stay fair. When there was a communist bloc, the two systems were keeping each other in check to some extent, he says in an interview at his office in Gdask. Now there is no control over the development of capitalism. Its like a road without traffic lights or road signs.

However, looking back at the economic transition, famously compared by him and others to turning fish soup back into an aquarium, the 76-year-old feels there are plenty of reasons to look positively on the past three decades. Already the fish are swimming, and theyre doing all right now, he says, with a smile.

This article is part of a series on possible solutions to some of the worlds most stubborn problems. What else should we cover? Email us at theupside@theguardian.com

Recent Comments