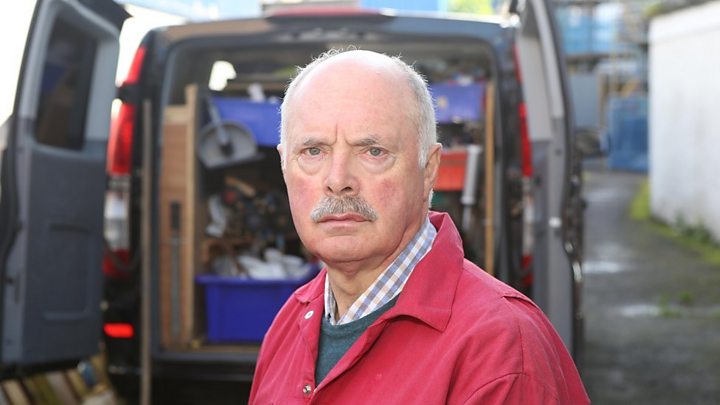

For decades plumbing firm boss Murray Menzies paid into a pension scheme for his workers at a time when it was not compulsory. But a series of complex changes to the law mean the 71-year-old is now being pursued for a huge “pension debt” to cover a shortfall in the shared fund he used.

It began with a phone call from the man at the pension fund. Murray Menzies owed them money. £1,198,300 to be precise.

“I thought he was joking,” recalls the semi-retired plumber from Inverness. “After a little while, when I realised he was being quite serious, I just thought it can’t be – it can’t possibly be.”

Mr Menzies, whose case was recently highlighted by The Herald newspaper, has no way of paying the money – selling his home and everything he owns would only cover a fraction of his “debt” to the pension fund.

What makes his sense of injustice sharper is that his only crime was trying to be a good employer.

Back in 1975, when he offered his small team of plumbers a workplace pension, there was no legal obligation to do so.

His handful of workers were signed up to the Edinburgh-based Plumbing Pensions scheme, one of the few schemes in the UK to be multi-employer, meaning it could be accessed by different, unconnected, employers and their employees.

For 40 years, Mr Menzies paid a monthly employers’ contribution, typically about £1,000. Then, four years ago, he decided to retire.

“I don’t employ anybody anymore. I was very happy in 2015 when I wrote my last pension cheque,” he said.

“I thought ‘great, another thing out of the way’ Then all of a sudden I got this letter saying I had triggered Section 75. I had no idea what they were talking about.”

He’s not alone. Some 560 employers across the UK who joined the Plumbing Pensions scheme are facing similar liabilities, many of them former small business owners who have no means of paying it off.

“We were the good guys – paying for a pension when it wasn’t law,” says Mr Menzies. “Talk about something coming back and biting you on the bum.”

What is Section 75 debt and why is this happening?

Image copyright BBC/Getty Images

Image copyright BBC/Getty Images Section 75 came about as a result of a sweeping review of pension regulation in the wake of the Robert Maxwell scandal in the 1990s.

Following the media tycoon’s death it emerged he had plundered millions from the Mirror Group pension scheme.

The Pensions Act 1995 introduced a series of reforms including a “minimum funding requirement” for pension funds. It also introduced something called “Section 75 pension debt”, which meant if an employer “departed” a scheme, they could still be pursued for any shortfall.

At the time, this wasn’t a problem for Plumbing Pensions, a well-respected multi-employer scheme that was recommended by trade associations and unions.

The minimum funding requirement was fairly relaxed and Plumbing Pensions was judged to be fully-funded.

But a few years later a pensions crisis involving Danish shipping giant Maersk prompted another shake-up.

Since 2005 far more stringent rules have been in force – and, by this new yardstick, Plumbing Pensions was deemed to be under-funded.

That meant the Section 75 debt law kicked in and under the rules anyone who “departed the scheme” found themselves liable for a share of the “shortfall”.

And because it was a “last man standing scheme”, those still in it had to pick up the liabilities of those who had already left – even though they had no connection with those businesses.

Image copyright Plumbing Pensions

Image copyright Plumbing Pensions “There’s nothing the scheme can do. The scheme is in a really difficult position,” she said.

“We recognise that the sums of money employers are being asked to pay are staggering and in some cases completely unaffordable – but if it doesn’t issue these debt notices, it faces financial penalties that could put the members’ benefits at risk.”

But a question that many of those affected are asking is why weren’t they told sooner?

From 2007 to 2009 there was a brief period when the law allowed members to get out of the scheme by paying as little as £1.

Those now facing huge bills say they were kept in the dark about this – and are only now learning about their “debt”.

Plumbing Pensions said that was partly down to the complexity of gathering data from thousands of individual employers.

It has also spent many years lobbying for an exemption from the law.

“When this law came in, it was recognised it didn’t work for the plumbing scheme and it would have terrible consequences for these employers,” Ms Yates added.

“So much time has been spent talking to government officials seeking ways to help the employers, while being fair to the members of the scheme.”

Glimmer of hope ‘scuppered by Brexit’

Alan Brown, MP for Kilmarnock in the last parliament, knows at first hand the impact this is having on small businesses. A local firm employing 20 people was forced to close because it had become unsellable.

The SNP politician introduced a private members bill last year, with cross-party support, which would have given these employers some protection – but amid the recent political turmoil, it has run into the sand.

His frustration is shared by the Scottish and Northern Ireland Plumbing Employers’ Federation (Snipef) which for years actively encouraged its members to sign up with Plumbing Pensions.

Snipef chief executive Fiona Hodgson has been lobbying for a law change – but she’s faced three changes of UK Pension Secretary in three years and with so much else going on politically, the chances of it being resolved any time soon appear slim.

“We’ve been doing our utmost to get something done about this but Brexit has scuppered it,” she said.

The Department for Work and Pensions spokesman said the rules were in place to ensure schemes were adequately funded.

He said: “We have a duty to protect members in their retirement, ensure schemes are properly funded and work with those employers who remain in a multi-employer scheme.

“We’ve introduced greater flexibility to help employers manage their debts.”

Without a political solution, the small businesses caught up in this are left in limbo.

“I’ve sat in my office here crying,” said Mr Dorwood. “I’ve spent two-and-a-half years not sleeping at night, sitting in here at four in the morning trying to find a solution. For a 51-year-old father-of-two who’s built a successful business it’s a disgrace.”

“All I’ve done is try to be a good employer,” said Mr Menzies. “I just try to carry on and hope that common sense will prevail.”

Read more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-50157515

Recent Comments