From Shackleton in the Antarctic to Edmund White on the Aids crisis, Emily Chappell rounds up stories of survival

I cant go on, Ill go on, is the weary conclusion of Samuel Becketts The Unnamable, a sentiment that, whether or not Beckett intended it, captures the inherent tension in acts of endurance. Whether that is cycling nearly 4,000 miles across Europe in less than a fortnight, or journeying through life itself, it can sometimes seem impossible or unbearable for mind, body and spirit to continue, and yet somehow they keep going, always fearing that the seemingly impossible may indeed prove to be so.

Failure was at the heart of Ernest Shackletons 1914 expedition to Antarctica, his ship Endurance crushed by pack ice. The journey, as recounted in his book South, was remarkable not only because the entire 28-man crew survived their estrangement from the world for 22 months, but also for the relative good humour Shackleton reports.

In The Rise of the Ultra Runners, Adharanand Finn gives us an inside view of the mind-boggling world of long-distance running, and perfectly captures the ebb and flow of a long race; the moments when you feel you cant take another step, chased by those fleeting periods when you believe you might run for ever. And Sarah Outen, in Dare to Do, tells us that the most enduring muscle of all is attitude. If you want to get there, you will.

But it aint necessarily so, argues Alex Hutchinson, exploring the curiously elastic limits of human performance in Endure. He delves meticulously into the mind over muscle conundrum of endurance do we fail because our body stops working, or is it our brain that makes us give up? And how can we train each of them to take us just a little bit further?

Endurance, of course, isnt only about athletics and adventure. Theres little glory in Dervla Murphys Where the Indus Is Young, in which she spends a winter in northern Pakistan with her six-year-old daughter. Murphy turns her gaze on the inhabitants of Baltistan, whose hardships are not chosen, as hers are, as well as detailing the quotidian but nonetheless excruciating ordeals of travel bureaucracy, kerosene shortages, illness and admitting the occasional tedium of her daughters company.

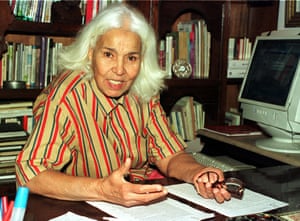

There is a stronger camaraderie in Nawal El Saadawis Memoirs from the Womens Prison began its life written with eyeliner on hoarded pieces of toilet paper, and follows the Egyptian author through a three-month incarceration for crimes against the state. In prison, a persons essence comes to light, she writes, suggesting that endurance consists of the parts of a person that remain when trauma or exhaustion have scraped away all pretence.

Some people endure unintentionally, sometimes even without wanting to go on. The protagonist of Edmund Whites autobiographical novel The Farewell Symphony looks back on the Aids crisis and the many men he loved, most of whom he knows or guesses must be dead by now. He invokes Haydns eponymous composition, where more and more of the musicians get up to leave the stage, blowing out their candles as they go. In the end just one violinist is still playing. Endurance is an act of survival, be it of a persons values and politics, their sense of humour, their will to go on or their very existence.

Where Theres a Will: Hope, Grief and Endurance in a Cycle Race Across a Continent by Emily Chappell is published by Pursuit.

Recent Comments