The California senators campaign began with a huge rally in her home state but factional infighting and lack of a clear message took their toll

Newspaper editors infamously prepare obituaries before their subjects have died, keeping them ominously in reserve until the moment of truth.

The writing was on the wall for Senator Kamala Harris last week when both the New York Times and Washington Post published political obituaries about a campaign in disarray.

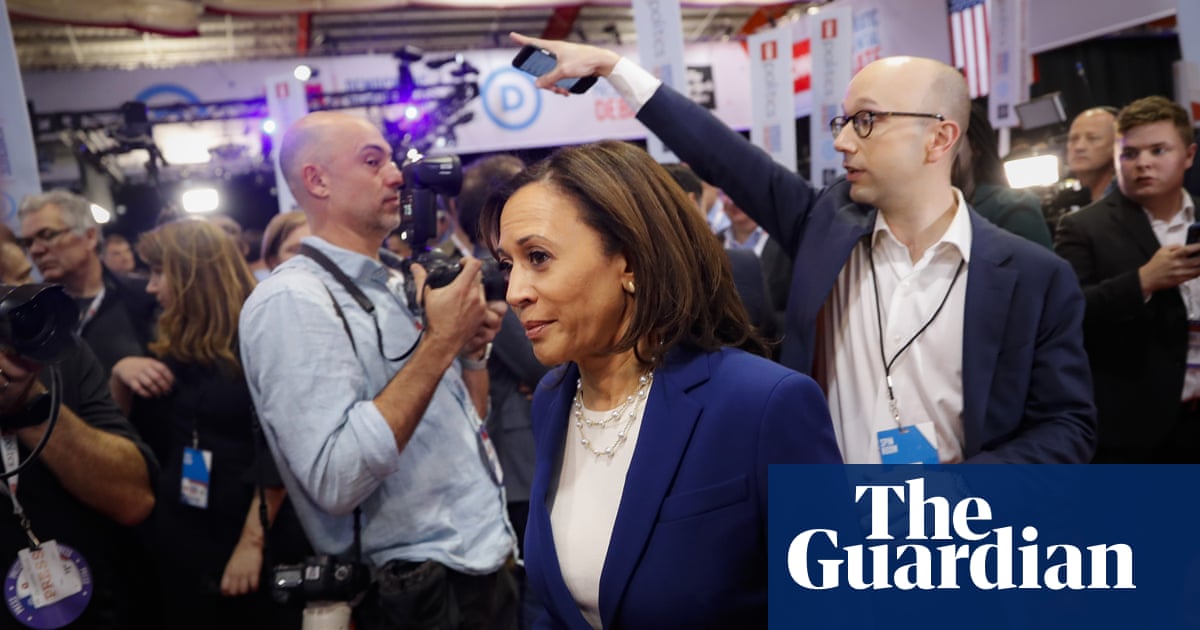

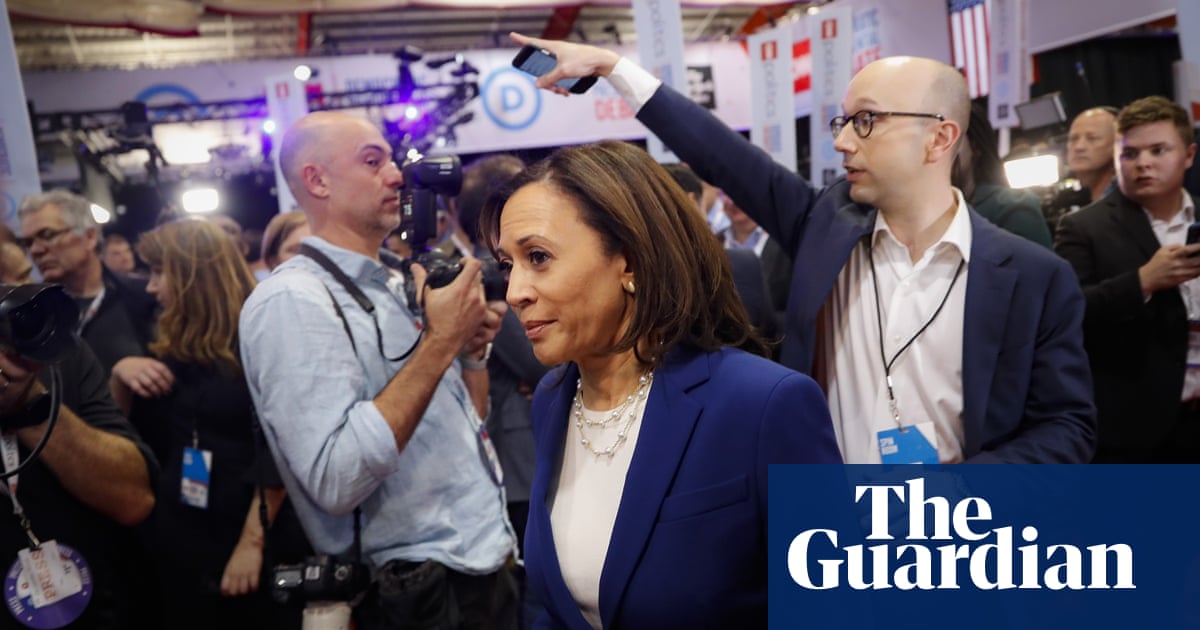

The death of the dream that a woman of colour could become the next US president was officially pronounced at 1.19pm on Tuesday in an email to supporters with the subject heading: I am suspending my campaign today.

Harris was the biggest name so far to withdraw from a crowded and volatile 2020 presidential race. When she launched her campaign at an outdoor rally in Oakland, California, in January, few in the crowd of more than 22,000 people could have guessed that she would be gone before Pete Buttigieg, mayor of South Bend, Indiana, or Andrew Yang, a tech entrepreneur and political novice.

In fact that rally was the high point. There was never a better moment in the Harris campaign. Apart from a classic debate soundbite, it was all downhill from there for a candidate whose campaign succumbed to factional infighting and whose lets have a conversation mantra was ill-suited to the political moment.

From my perspective, she never connected with the electorate, says Moe Vela, a former senior adviser to Joe Biden and board director for TransparentBusiness. I dont think voters ever got to see her true and authentic self due to vacillating policy stances and plans. There was an inconsistency to her at a time when voters are seeking stability.

Combining that with a campaign team that appeared to be in turmoil, you have a recipe for disaster.

On paper, Harris, 55, should have been the ideal antidote to Donald Trump: a female Barack Obama who could rebuild his coalition. Like the former president, she is mixed race (her father from Jamaica, her mother from India), spent part of her childhood abroad (in Canada) and became a lawyer, then the first black US senator in Californias history.

In congressional hearings, Harris had tormented Jeff Sessions and other figures from the Trump administration. She seemed to be the ideal person to cross-examine Trump on a debate stage and prosecute the case against his corruption, misogyny and racism.

Harris raised an impressive $12m in the first three months of her campaign and quickly secured major endorsements in her home state, which offers the biggest haul of delegates in the Democratic primary contest.

But as the competition grew, Harriss fundraising flatlined and the media shone its light elsewhere. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren pulled in tens of millions of dollars from grassroots supporters, while Buttigieg drew money from traditional donors.

Some detected bias. LaTosha Brown, co-founder of Black Voters Matter, said: I feel in many ways the women, and Kamala in particular as a black woman, were not treated the same as the white men in this race. There was an environment of sexism and racism.

In recent weeks, reports emerged that Harriss staff complained about being badly treated; another female candidate, Senator Amy Klobuchar, has faced similar allegations. Brown commented: I only hear complaints about the women. Either all the men are just nice bosses or they are not judged by the same standard. I have not heard a real critique of what kind of managers the white men are.

The white men can just turn up and be charismatic and thats enough. For some reason, a woman has to be an extreme nurturer or a stellar boss. When Pete Buttigieg had a surge, he got all kind of press. I never saw that kind of headline for her; she always came in from behind. If you look at how she was treated as a candidate, it was completely different.

Others argue that Harris, who constantly stressed the need to speak the truth on race and other issues, lacked ideology and seemed vague and inconsistent on policy.

Like other Democrats, she stumbled over the issue of healthcare, at first indicating that she supported abolishing private health insurance, then back-pedalling and claiming she had misheard a question at one of the debates. She eventually released a plan that preserved a role for private insurance.

But in June, struggling to break former vice-president Joe Bidens lock on African American voters, Harris produced arguably the stand-out moment of the primary debates so far. She accused Biden of past opposition to bussing, an effort to racially integrate government schools.

There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bussed to school every day, Harris said, before delivering the killer line: That little girl was me.

Bidens head snapped around to look at her. It was a blow to the solar plexus. He tried to defend himself but, up against the clock, blurted out: My time is up. Im sorry.

The line, That little girl was me, rapidly appeared on T-shirts and a Saturday Night Live parody. However, it also produced sympathy for Biden and a backlash that denied Harris momentum. In the following debates, she seemed to fade into the background.

Other catchphrases or stunts never quite took off. There was a 3am agenda about the hopes and fears that wake people up at three in the morning. It echoed, perhaps unfortunately, Hillary Clintons 2008 ad about who is best qualified to answer a 3am phone call in a crisis.

And Harris could never quite escape progressive scepticism about her past. She started her career in Oakland, serving as a local prosecutor in the 1990s, before becoming the first African American and the first woman elected as San Francisco district attorney in 2003 and as California attorney general in 2010.

During her presidential run, Harris billed herself as a progressive prosecutor. She titled her first book Smart on Crime looking to leave the hard on crime and soft on crime stereotypes behind.

Yet Harriss contradictory, complicated record as a prosecutor in California corroded her presidential bid. Even as she started programmes to steer low-level drug offenders away from prison, she boasted about increasing conviction rates and supported fellow prosecutors accused of misconduct.

Her anti-truancy programme, which led to the arrest of parents whose children were chronically absent, her inaction on police brutality and her opposition to decriminalising sex work also drew criticism from progressive voters. Eventually, she decided to embrace this biography with the slogan Justice Is on the Ballot, and by vowing to prosecute the case against a criminal president.

California, which should have been a stronghold, proved problematic in other ways. Bill Whalen, a fellow at the Hoover Institution thinktank at Stanford University, wrote in the Washington Post last month: Analysts seeking to understand the Kamala Harris flop need look no further than Harriss ostensible selling point: her record in California. After nearly three years as the states junior senator, Harris doesnt have much to show for herself.

Take, for example, Harriss signature policy issue. What is it? Her Democratic colleague, Dianne Feinstein, is known among California voters for her policy-grinding: on assault weapons bans; protecting the Golden States forests, deserts and lakes; and the occasional supreme court nomination brouhaha.

The downward spiral was clear and irreversible. Harris finished September with $9m in cash, according to finance disclosures; Warren had nearly $26m at the same stage. Last month Harriss campaign announced it would fire staff at its Baltimore headquarters and move some people from other early states to Iowa for a last stand.

Aides shared grievances with the media, including questions over whether Harriss sister, Maya, the campaign chairwoman, had too much influence. Several senior aides quit to join other campaigns.

One of them, Kelly Mehlenbacher, wrote in a resignation letter obtained by the New York Times: Because we have refused to confront our mistakes, foster an environment of critical thinking and honest feedback, or trust the expertise of talented staff, we find ourselves making the same unforced errors over and over.

Harris cited lack of financial resources for her decision to terminate the campaign now. She had qualified for this months debate, which will be held in her home state, but her exit, which represents her first defeat as a political candidate, puts the party at risk of a debate featuring white contenders only a dismal look for a party that had the most diverse field in political history.

This is America, muses Brown. All of what I want to believe about America, she continues to show how embedded racism is in the political system.

Additional reporting by Maanvi Singh in Oakland

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/dec/03/kamal-harris-campaign-analysis-democrats-2020

Recent Comments