The 1918 influenza pandemic killed my great-grandmother and her daughter. I thought this was merely tragic until I found myself leaving on the heels of another plague, a week before lockdown

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed my great-grandmother Julia and her oldest daughter, Goldie. They were both young, in their early 40s and 20s, and lived in west Texas during one of the biggest oil booms in American history, one that brought tens of thousands to the towns where they lived, and where the plague spread like grassfire.

For the longest time Id thought of this family history as merely tragic a pin placed along a timeline of calamities weve endured through the generations. Their deaths from influenza had existed as an unlived abstraction. That is, until I found myself fleeing New York City with my wife, children and dog on the heels of another plague. The city had already begun to close in on itself. The kids school had shuttered the previous day, along with the seminary where Im currently studying.

Any thoughts of staying had quickly crumbled after seeing the lines stretch around the grocery store. With the car stuffed with everything it can hold, including camping gear and the contents from our pantry and medicine cabinets strapped to the roof, we head west, back home toward Texas. Later that week the governor would order New Yorkers to stay indoors and self-isolate.

As we cross the George Washington Bridge I find a prayer of gratitude for the ability to even leave. Yet despite this privilege, I know we are not truly safe no matter the distance. And this fear is one I recognize not from my own experience but from those Ive covered as a journalist, people who fled places such as Congo and Somalia and Guatemala and for whom these decisions are tragically commonplace. If anything, the plague has a way of showing us that our exceptionalism is a myth. It shakes us awake with terrifying perspective and shows us who we truly are. As we flee New York and abandon our work and seemingly important plans, I know that I am but a speck of dust beneath a deadly settling fog. I am history made new. Out on the road, I enter communion with the ghosts of my kin.

My great-grandparents were homeless when the first cases of influenza reached Texas in September 1918. Already it had ripped through Europe, killing thousands of servicemen training and fighting the war. By the end of summer, the plague had reached cities along the eastern seaboard, where it would kill more than 30,000 New Yorkers. In Philadelphia, bodies would be stacked so high in the morgues that veteran embalmers recoiled and refused to enter, as one historian noted. At the same time, the virus traveled west on the railroads the same way that we and many others are doing now along the interstate highways, unsure if were spreading it from town to town when we pump our gas or hand our credit cards through the drive-thru windows.

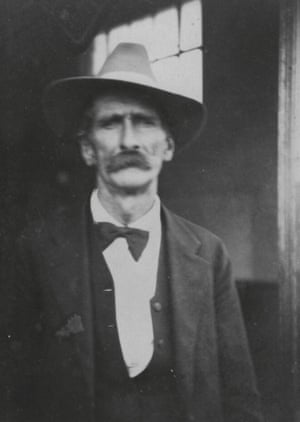

It reached Texas in the midst of a crippling three-year drought, one that had wiped out my familys farm along with countless others. After the bank foreclosed on their 71 acres near the town of Eastland, my great-grandfather John Lewis Mealer and his wife, Julia, had packed their four children and belongings into a horse-drawn wagon and joined thousands of other refugees seeking shelter.

By summer 1918, the roadside between Eastland and Dallas swarmed with homeless families who were broke, hungry and desperate. A layer of dust covered everything, only deepening the misery.

They have exhausted their own resources and now the people are brought to the point of starvation with no further hopes in the west, the state representative DJ Neill warned the Texas legislature that August. Many thousands have turned their faces eastward, homeless, friendless, moneyless The people must be fed or leave the country or die.

Yet as thousands fled eastward, many more were coming the other way. In January 1917, a major oil discovery near the town of Ranger, just 10 miles from my familys land, had sparked the biggest oil boom in the world. Its timing couldnt have been more perfect for the ongoing war in Europe, where allied forces were dangerously low on fuel, so much that Walter Long, the British secretary of state for the colonies, had told the House of Commons that fall that oil is probably more important at this moment than anything else.

The oil boom swelled the population of Ranger from 1,000 to 30,000 in less than a year. Tent cities and tar-paper shacks rose near the rigs and along the outskirts of town. In the boarding houses, men slept in shifts for lack of beds. Trainloads of boomers and servicemen pulled in each day, some clinging to the roofs. When the plague arrived in September it had easy pickings. In less than a month Ranger reported more than 2,500 cases. El Paso had 4,000 cases and over 400 deaths.

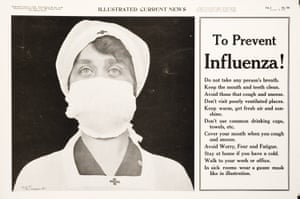

By October, the American Red Cross issued a bulletin that was printed in newspapers throughout west Texas listing the various symptoms: bloodshot eyes and high fever, pain in the eyes, ears, head or back, and dizziness. It advised caregivers to wear aprons over clothing and use rags or paper napkins for any sputum or running of the eyes and nose, and to burn them straightaway. It warned against large gatherings and overcrowded homes and offered a jingle for easy memory: Cover up each cough and sneeze, if you dont youll spread disease.

In Abilene, 65 miles west of Ranger, an estimated one in three residents came down with the flu. In many of the bigger towns, movie theaters, churches and schools closed for weeks. Engines went quiet as the workforce was laid up in bed. Walking canes are very popular among the victim of the flu, the Abilene Reporter wrote, noting that lingering pain in the lower extremities had left legions of hearty and capable fellows hobbling like old men. Recoverees jokingly referred to their new fraternity as the Ancient and Honorable Society of Influenza Victims.

Just as Donald Trump and Texass lieutenant governor, Dan Patrick, have prioritized the economy over public health, theres no indication that places like Ranger and the surrounding boomtowns closed shop now that money was pouring in. Officials in nearby Brownwood kept schools and businesses open, defying warnings. Local doctors issued conflicting protocols, and in place of real information many newspapers ran paid editorials that pushed a powerful reconstructive tonic called Tanlac to ward off the plague.

By the end of October, state health officials reported that more than 6,000 Texans had died.

Disinformation bred fear. Just as Trumps insistence on calling Covid-19 the Chinese virus exacerbates the uptick in assaults on Asian Americans, the same held true in west Texas in 1918. According to relatives, amid this rampant fear and confusion my great-grandparents found shelter at a house in a nearby town. But when the neighbors discovered their presence, a mob formed outside the home and some men dragged out Julias belongings to burn in the street. It took the local sheriff arriving to restore peace. The story had always confused me. According to relatives, Julia may have had tuberculosis toward the end of her life, which was fairly common at the time, but I wondered, why would a mob try to burn her clothes?

But after having to explain to our kids why so many people were wearing masks on the streets of New York and why they couldnt touch the subway railings or their faces, or why the apartment always smelled of bleach and our hands were cracked from so many washings, that story about Julia began to make perfect sense. You burn something in order to kill it, to neutralize it into ashes.

She died sometime after that incident. The only story about her death that survived is that her coffin was placed on a table wherever they were staying, and their youngest boy, my grandfather Robert Odell, who was four at the time, had crawled beneath it and cried himself to sleep.

For years I looked in vain for her grave or any record of her death. One of my uncles says they most likely buried her on the road, because thats what people did back then. People who were poor and landless and thus more vulnerable. Im not sure where John Lewis took his four children after burying his wife, but it was far. Perhaps he was running from the thing that had stalked his family and wanted to protect his children. But his efforts were in vain.

In early January 1919, he received word that his oldest daughter, Goldie, who was 24 and married, had fallen ill in Desdemona, a town not far from Ranger. Desdemona was the latest bonanza where gushers were left to blow unattended and oil ran ankle deep through the streets and filled the creeks and gullies. It took two weeks of hard travel for John Lewis and the kids to reach Desdemona. But by the time they arrived she was already dead and buried, having succumbed to pneumonia brought on by the flu.

The Cracker Barrel restaurant in Crossville, Tennessee, is packed on a Friday night. I sit there waiting for our to-go order and try not to breathe or touch anything, listening as one party after another pays their check with the chatty cashier and never once mentions the virus.

That evening at our hotel, the clerk tells my wife the media is overblowing the whole thing in order to bring down Trump, while on Fox News the hosts are still excusing Covid-19 as a hoax and a death knell to a booming economy. I know that during the influenza epidemic some publishers in west Texas were reluctant to report death tolls in their newspapers for fear it would scare away investors to their boom towns, and as a result thousands continued to pour in to make fortunes and eat steaks in the new hotels, while others like John Lewis buried their wives and daughters.

As I drive I find myself communing with this man, asking what he told his children as their mother lay dying in a wagon bed, what words he used to comfort her in her last moments. Could they even afford a doctor, or was their poverty such that Julia just died only to be buried in a field or culvert because that was the fate of the poor?

We seek answers from the dead through what Abraham Lincoln called the mystic chords of memory, which connect human experience through the ages. The plague that now stalks our country connects me with John Lewis just as it tethers me to folks half a world away. It gives me sudden new perspective of the Congolese parents I so often interviewed in displacement camps during the war, men and women who described the stress and anxiety that clawed at their guts from having to surrender to a great unknown, not knowing if they or their loved ones would ever see the other side. Im reminded of the Central American families I walked alongside last year in the migrant caravan, who one day held jobs and ran businesses and the next found themselves in a strange country waiting in food lines to feed their children.

Yet I know that compared with John Lewis and the people I described, most Americans like me will fare remarkably better. We have the resources that allow us to leave places like New York City or afford homes replete with the necessary groceries, laptops and streaming devices that make quarantine a relatively comfortable ordeal. And if and when we get sick, were fortunate to have a healthcare system that, while currently overstressed, is comparatively superior.

And still thousands will die in our cities and home towns. The poor and dispossessed will suffer disproportionately, and people we know and love will get sick and not make it. And when this happens we will curse an absent God and blame our leaders. Facebook and Twitter will register the grief and anger, but in the end it will connect us in ways we cant foresee. For this virus is a hard truth coming down the pike, the way hard truths have done for centuries. They reveal to us the absurdity of our presumptions, the bankruptcy of our entitlement. That our borders are meaningless and the stories we have told ourselves are only stories. When stripped away, we are collectively naked and lonely and afraid under the sun, driving a minivan through Dallas for the first time with no traffic. That we have forgotten what its like to be vulnerable and to hurt and to see that in others, which is where God will always be found.

Or this is my prayer anyway as I drive seeking counsel from ghosts, looking in the rearview every so often to find that everyone is sound asleep.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/02/coronavirus-1918-influenza-epidemic-fleeing-new-york

Recent Comments